Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

Five Reasons Why American Schools Are Still Separate and Unequal, 64 Years After Brown v. Board

Today is the 64th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the landmark Supreme Court decision that outlawed de jure segregation–the kind of explicit and intentional segregation reflected in “Whites Only” signs and laws that directly mandated racial segregation in public spaces like schools. As people who believe that all children, regardless of race, class, gender, disability, or any other facet of their identity deserve an equal chance to reach their potential, we celebrate and honor that victory. But we also recognize that this work is far from over. After all, in a society founded on genocide and enslavement followed by decades of Jim Crow, there are still plenty of ways to perpetuate school segregation without ever having to explicitly say that’s what you’re doing. Here are just five of the still-too-numerous reasons American schools remain separate and unequal, plus ways we as a society can change that.

Residential segregation. In both conscious and unconscious ways, real estate developers, home sellers, and public officials still engage in discriminatory practices around housing and transportation planning, and many white renters and home buyers still choose to avoid living near people of different races. And when communities are racially segregated, local schools tend to be racially segregated as well. But they don’t have to be. Public officials could make it a priority to integrate schools and communities by rethinking district boundaries and funding formulas. (The fact that various creative strategies for boosting residential and educational integration aren’t typically on their agenda is very telling.)

Regressive courts. Those of us who believe in equality and justice tend to be grateful for landmark rulings like Brown. But the civil rights-era victories advocates won in and outside of the courtroom triggered a huge backlash among angry individuals committed to white (male) supremacy. One of their most successful strategies has been their sustained efforts to stack our judicial branch with judges committed to rolling back fledgling progress toward school integration and full equality before the law. In the following decades, many of these conservative judges prematurely released school districts from desegregation orders, limited which strategies districts and communities could use to achieve integration, and made it harder for people harmed by segregation to challenge it. Their success stands as a critical reminder that courts matter. We who believe in freedom have to pay attention to our local and state courts, and elect officials who will appoint or confirm judges who can be trusted to rule in society’s best interest.

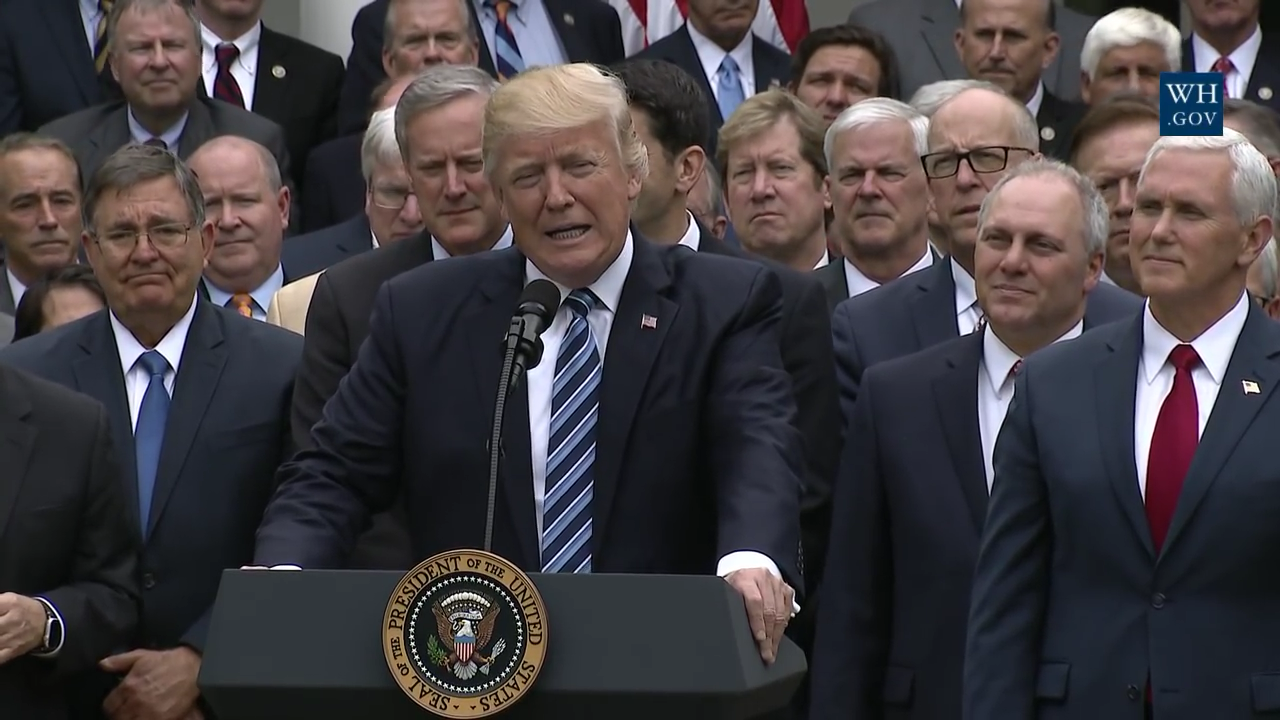

Problems with federal oversight. Historically, the power of the federal government has been one of the few checks on the power of racist local and state leaders and voters who prefer segregated school districts and communities. But whether they use that power to promote equality or injustice depends a lot on who’s in charge. When led by more egalitarian appointees, federal agencies like the Department of Justice and the United States Department of Education (USED) have helped protect students of color. But when led by less egalitarian appointees, these same agencies have reinforced discrimination by ignoring school segregation, weakening enforcement of important civil rights laws, and declining to thoroughly investigate systemic violations of those laws. For example, during the second Bush administration, USED’s former Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights Kenneth Marcus actively opposed race-conscious efforts to increase school integration, and was responsible for regulations that allowed sex-segregated educational programs to spread. He’s now been nominated by Donald Trump to return to that position, where he’d likely do even more harm. We have to urge our Senators to reject nominees like Marcus, and demand that they do everything they can to constrain already-confirmed but deeply problematic officials like Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and Attorney General Jeff Sessions.

Biased pedagogical practices and discipline policies. Schools cannot be considered truly integrated if students of different races learn in separate and unequal conditions within the school walls, or if students of color are excluded from school outright. But that’s what happens when educators don’t address their own implicit and explicit biases. Their subjective interpretations of students’ learning and behavior, combined with pressure from higher-status parents, frequently results in students of color being disproportionately tracked into less rigorous courses where they receive fewer opportunities than their white counterparts. Meanwhile, in every state, Black students are frequently pulled out of class, suspended, and/or violently arrested for vague and capricious reasons like “talking back” or “having an attitude,” or are punished for what they look like or wear. Not only does this rob students of their right to an education, it puts them on a pathway to the criminal justice system. In order to make equal opportunity a reality, we have to push our school districts and teacher education programs to ensure all school employees and educators unpack their own biases and learn ways to build safe school communities rooted in restorative justice rather than harsh punishment, exclusion, and violence.

Biased community members. Just as white people chased Elizabeth Eckford for daring to attend classes at Little Rock Central High School in 1957, white parents across the political spectrum still furiously oppose efforts to integrate schools. They may speak in more coded language than their ancestors, couching their concerns in the language of “safety,” property values, or test scores instead of overt hatred. But the bottom line remains the same: many white parents just don’t want their children to go to school with Black kids. From the wealthy Upper West Side of Manhattan, to suburban St. Louis, to Tuscaloosa, Alabama and beyond, some white families have responded to the possibility of school integration with such vitriol and fury that many politicians are afraid to even utter the word “segregation,” much less propose serious plans to address it.

But we cannot let fear stop us from doing what’s right. All of us, white people especially, must confront our own biases and overcome our reluctance to talk openly and honestly about the ways racism still shapes our lives and public institutions. Unaddressed racial hostility remains one of the biggest hurdles to truly eliminating “separate, but equal” schools, but we can change that. We can decide to be better. We can become the generation to actually integrate schools, if we educate ourselves and our communities, and push our leaders to name this problem and take bold steps to solve it.