What Can a Degree Do for You? A Lot Less, if You’re a Woman

Thanks to the gains feminism has made over the past few decades, young women are no longer enrolling in college to get their “Mrs.” degree.

Studies show that not only are women getting Bachelor’s degrees, but they are out-graduating men–and have been for some time. For the most part, this holds true for women of color: 41.6 percent of Black women, 67.7 percent of Asian women, and 40.4 percent of Latinas are enrolled in post-secondary education.

| According the Let Her Learn report, 86% of girls said they wanted to go to a 4-year college and 67% wanted to go to graduate school. |

The Cost of Higher Education

While society generally praises women’s increased higher education enrollment as a sign of progress, there is more to the story.

Women of color are graduating from college at increasing rates. Yet Latina and Black women are more likely than white and Asian borrowers to accrue crippling student loan debt. A recent report shows that women take on more student loan debt than men. Because of the wealth gap, the wage gap, and women’s overrepresentation in low-wage jobs, women have less disposable income to repay their loans. As a result, they account for more than $800 billion of the outstanding student loan debt, which is nearly two-thirds of the total student loan debt. This research also shows that Black and Latina women face particular difficulty repaying student loans. For example, 57 percent of Black women repaying student loans said they were unable to pay for their essential needs.

To make matters worse, women of color are targeted for recruitment by for-profit colleges, which exploit race, class, and gender inequalities by gearing their advertising toward students who qualify for the most financial aid. Many students at for-profit schools end up dropping out before graduation, walking away with nontransferable credits and no degree to fall back on–and loads of debt.

But there’s a reason why women of color are pursuing higher education in spite of all these challenges. Certainly, these women want to pursue opportunities in higher education but most women need to pursue higher education in order to get a job—at least the kind of job that will allow them to make ends meet and set them up for future success.

Education and Employment Challenges

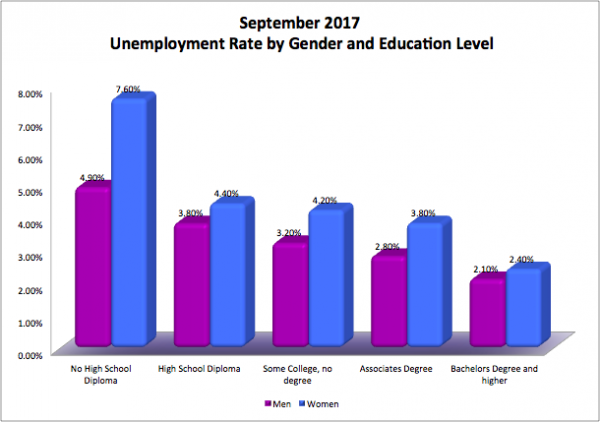

This month’s jobs report makes it clear: graduating from college increases employment rates—especially for women and even more so for women of color. Women without a high school diploma were 3.17 times more likely to be unemployed than women with a bachelor’s degree or higher. The difference between the unemployment rate of women without a high school diploma and women with a Bachelor’s degree or more was 5.2 percentage points, while the difference between men without a high school diploma and men with a Bachelor’s degree or more was only 2.8 percentage points. In other words, women have the most to gain–in terms of employment prospects–by graduating from college.

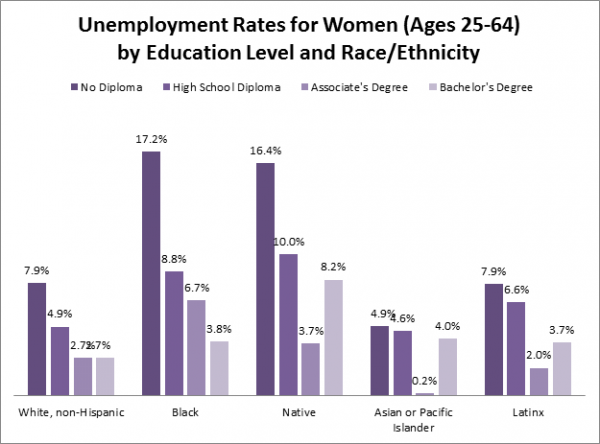

These differences in unemployment rates are even larger for some women of color. Black and Native women without a high school diploma had unemployment rates of 17.2 percent and 16.4 percent respectively. A Bachelor’s degree makes these unemployment rates fall more than 13 points for Black women and more than 8 points for Native women.

Women also faced a higher unemployment rate in September than equally educated men. Although these differences narrowed with an increase in education, even women with degrees are struggling to close the unemployment gender gap. Men who have a Bachelor’s degree or higher face an unemployment rate of 2.1 percent, compared to women who have an unemployment rate of 2.4 percent. Even when equally educated, women still face more difficulty finding jobs than men.

Long-term Effects

Wealth is one long-term effect of women’s educational attainment that varies by race. You can calculate wealth, or a person’s net worth, by subtracting debts from total assets. While there is a lot of focus on the race and gender wage gaps, race and gender wealth gaps can tell us a lot about what kinds of financial safety nets families have access to, especially during times of emergency.

Recent reports illustrate that there is women of color experience a staggering wealth gap. The average unmarried white man has $28,900 in wealth, while the average unmarried Black female has only $200. What women of color experience is a multiplicative oppression: the wealth gap x the wage gap means the loss of lots of income and wealth over a woman of color’s lifetime.

Historically, one way women have acquired wealth is through marrying men; men typically have higher incomes, assets, savings, and other benefits down the line (including Social Security), and marriage gives women access to this wealth. However, this is less the case today due to high divorce rates, increased rates of single motherhood, and women choosing to marry later in life (or not at all).

When educated women do marry men, they tend to marry someone who has a similar educational status, which means both spouses benefit from the other’s enhanced ability to build wealth. But, this is less true for Black women for a variety of reasons, one of them being that Black women are more likely than Black men to get college degrees. Thus, even this traditional (and inequitable) method of building wealth through marriage to a man is relatively closed off to Black women.

Ultimately, while women are increasingly educated, the impact of that education on employment and financial security varies by race. Even as women of color struggle to close the wage gap they must also pay for higher education despite having little wealth to pull from and despite facing higher unemployment rates. This is exactly why policy solutions for inequities in education and the workplace must remain squarely focused on the experiences of women of color.