Girls are the fastest growing population in the juvenile justice (JJ) system, with girls of color, LGBT and gender nonconforming youth, and girls with disabilities being overrepresented relative to school enrollment or share of the overall population. For instance, Black girls make up 15 percent of girls enrolled in public schools but 30.8 percent of girls in juvenile justice center schools. Girls who enter the juvenile justice system are likely to have suffered sexual abuse, violence, and other trauma; they also are often involved in the child welfare system. Sadly, they typically do not have the supports and stability they need to help them cope with their trauma, which can lead to behavior such as running away or substance abuse. These behaviors in turn may result in their involvement with the juvenile justice system, especially given that girls are particularly likely to be detained for status offenses—conduct that is only illegal when committed by youth, such as truancy, running away, or violating curfew.

Girls are the fastest growing population in the juvenile justice (JJ) system, with girls of color, LGBT and gender nonconforming youth, and girls with disabilities being overrepresented relative to school enrollment or share of the overall population. For instance, Black girls make up 15 percent of girls enrolled in public schools but 30.8 percent of girls in juvenile justice center schools. Girls who enter the juvenile justice system are likely to have suffered sexual abuse, violence, and other trauma; they also are often involved in the child welfare system. Sadly, they typically do not have the supports and stability they need to help them cope with their trauma, which can lead to behavior such as running away or substance abuse. These behaviors in turn may result in their involvement with the juvenile justice system, especially given that girls are particularly likely to be detained for status offenses—conduct that is only illegal when committed by youth, such as truancy, running away, or violating curfew.

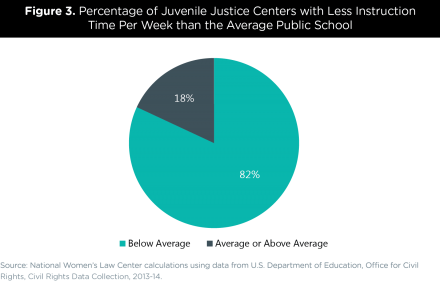

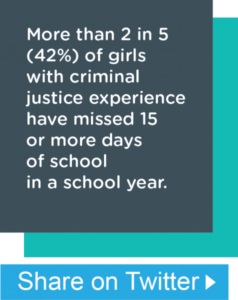

Once they are incarcerated, girls face a number of additional barriers  resulting from a system that was designed around boys and has rarely focused on the unique experiences and needs of girls. Girls involved in the juvenile justice system do not receive the kind of trauma-informed, gender-responsive support they need, which leads to poor mental and physical health outcomes and a risk of repeated criminal justice system involvement. Girls also face a number of educational barriers when confined, including juvenile justice centers’ lack of accountability for student outcomes, a lack of access to teachers, less instructional time, and difficulty returning to school once released.

resulting from a system that was designed around boys and has rarely focused on the unique experiences and needs of girls. Girls involved in the juvenile justice system do not receive the kind of trauma-informed, gender-responsive support they need, which leads to poor mental and physical health outcomes and a risk of repeated criminal justice system involvement. Girls also face a number of educational barriers when confined, including juvenile justice centers’ lack of accountability for student outcomes, a lack of access to teachers, less instructional time, and difficulty returning to school once released.