Fertility care is necessary reproductive health care that helps individuals and couples have children or

preserve their ability to have children in the future. But these services are often prohibitively expensive, and Black women, who are both more likely to experience infertility and have fewer financial resources, face disproportionate barriers to accessing this critical care. Comprehensive fertility coverage, which reduces financial barriers and improves access to this necessary care, is critical for the advancement of reproductive justice for Black women.

Fertility Challenges for Black Women

Black women experience disproportionately high rates of infertility.

In the United States, non-Hispanic Black women are almost twice as likely as either Hispanic or non-Hispanic white women to experience infertility.1 Black women have higher incidences of medical conditions that can cause infertility, such as uterine fibroids,2 a condition that can increase infertility risk and contribute to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Black women also experience higher rates of tubal factor infertility than white women.3 Tubal factor infertility can be caused by a range of conditions, including pelvic inflammatory disease and endometriosis.4 Pelvic inflammatory disease is more prevalent in Black women,5 and endometriosis in Black women is commonly misdiagnosed as pelvic inflammatory disease and inadequately treated,6 likely due to implicit and explicit racial and gender bias in health care.7 Black women are also more likely to be exposed to environmental toxins that harm fertility, such as industrial pollutants and water contaminated with lead or endocrine-disrupting chemicals.8

Access to fertility care is critical for Black women across varied identities and circumstances—including for cisgender and transgender Black women and those with or without partners.

- Black women may require timely referral and treatment for infertility-related conditions like uterine fibroids.9

- Black women may be unable to achieve pregnancy with their partner and require fertility medications or treatments like in vitro fertilization (IVF) or intrauterine insemination.

- Black women in LGBTQ+ couples or who are single may need to use donor eggs or sperm, donated embryos, or even work with a surrogate to achieve pregnancy.

- Fertility preservation services may be needed to protect or save eggs, sperm, or other reproductive tissue, including before medical treatments that may cause a risk of impairment to fertility, such as gender affirming care or chemotherapy or radiation for cancer.10

No matter who seeks fertility care, or their reasons behind it, every person deserves to access this necessary care without cost being a barrier. Comprehensive fertility care insurance coverage reduces financial barriers to care, thereby improving access for Black women and other under-resourced communities.

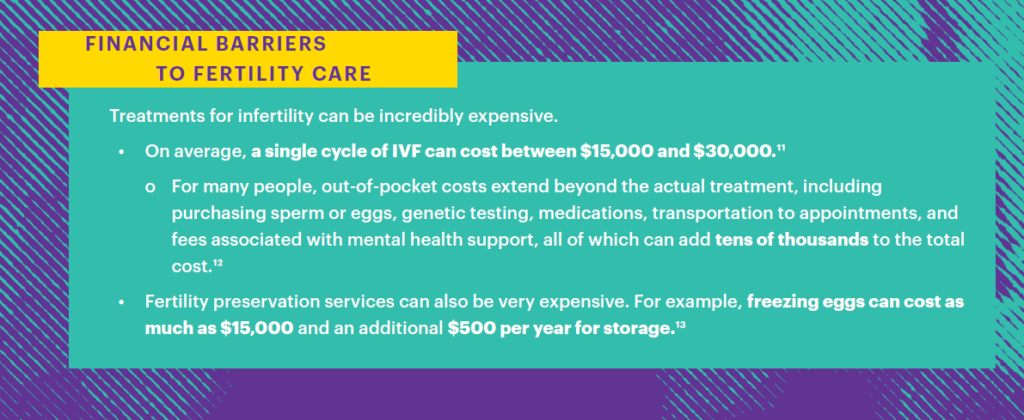

Exorbitant fertility care costs prevent many under-resourced people from getting the care they need. People with fewer financial resources—disproportionately Black women and other women of color, women with disabilities, immigrant women, and LGBTQI+ individuals14—are less likely to have comprehensive fertility coverage and are less likely to afford the high costs of fertility care.15 Black women in particular face notable wealth and wage gaps due to racism and sexism in the labor market,16 unaffordable and inaccessible housing, food, and childcare,17 and other systemic and structural barriers such as inequitable education and wealth accumulation.18 The resulting stark income and resource inequities19 compound harm to Black women who, as discussed, experience disproportionate rates of infertility.

Comprehensive fertility care insurance requirements are particularly important to increase equitable access. For some Black women insurance coverage of fertility care could mean the difference between prompt and quality fertility care or no care at all. For decades, lawmakers across the country have championed legislation aimed at addressing financial barriers to fertility care. Currently, 22 states and Washington, D.C. have passed fertility insurance coverage laws, with some of these laws in place since the 1980s.24 Only Illinois, Maryland, Montana, New York, Oklahoma, Utah, and Washington, D.C. have laws relating to Medicaid coverage of infertility treatments and fertility preservation.25

Health Outcomes and Why Coverage Matters

Comprehensive coverage of fertility care may also help reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes, which is of critical importance for Black women, who face disproportionately high maternal mortality and morbidity and infant mortality.

Limiting adverse pregnancy outcomes is an imperative for Black women, who face a maternal mortality rate nearly 3.5 times higher than white women26 and higher rates of severe maternal morbidity, miscarriage, stillbirths and infant mortality.27 Ensuring comprehensive coverage of the full-range of fertility services, such as genetic testing and embryo transfers, could mitigate contributors to poor pregnancy-related outcomes and play a critical role in addressing the health disparities faced by Black women.

Preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) is a screening test used when selecting embryos for transfer. Certain genetic conditions can increase the risk of a failed IVF cycle or miscarriage, with embryos of patients over the age of 37 more likely to have these conditions.28 PGT is typically very costly (like most fertility services) and usually not covered by insurance. For example, one form of this genetic testing typically costs around $5,000 per IVF cycle.29

Frozen embryo transfer can also amount to thousands of dollars, ranging from $3,000 to $5,000 on average.30 A pregnant person who is paying for their treatment entirely out-of-pocket may be more likely to elect to transfer multiple embryos to avoid the cost of multiple transfers.31 Transferring more than one embryo puts a pregnant person at risk for multiple pregnancies and births, which can have adverse consequences for both the pregnant person and their infants.32 For example, multiple pregnancies increase the pregnant person’s risk of miscarriage and preeclampsia, a leading cause of maternal mortality, and commonly result in preterm births.33

Making fertility care services more affordable could potentially reduce risk of pregnancy complications.34 Miscarriages can cause enduring and even life-threatening health consequences,35 with harms likely exacerbated for Black women who face disproportionate racism and mistreatment when receiving care.36 Reducing poor pregnancy-related outcomes like miscarriage is especially important considering that nearly 25% of all U.S. counties lack adequate access to abortion care and other emergency pregnancy care that may be needed to manage a miscarriage.37 Black women in these areas face compounded barriers to obtaining lifesaving care when needed. Comprehensive insurance coverage can also help patients face fewer financial pressures when making decisions regarding their fertility care, such as how many embryos to transfer or whether they would benefit from genetic screening.38

***

Cost should never be a barrier to obtaining necessary care. Comprehensive insurance coverage for fertility care is critical to increasing equitable access for Black women and other traditionally under-resourced communities. Lawmakers, advocates, and other stakeholders should view fertility coverage as an essential step toward reproductive justice for Black women and other underserved groups.

Find the official factsheet here.

Endnotes

1 Anjani Chandra, Casey E. Copen, and Elizabeth Hervey Stephen, “Infertility and Impaired Fecundity in the United States, 1982–2010: Data From the National Survey of Family Growth,” National Health Statistics Reports, no. 67 (August 14, 2013), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr067.pdf. For this data, infertility is defined as “a lack of pregnancy in the 12 months prior to survey, despite having had unprotected sexual intercourse in each of those months with the same husband or partner.” We recognize that this definition is narrow in scope and is not inclusive of all circumstances in which someone may require fertility care, such as single women or women in LGBTQ+ relationships. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) definition of infertility that was updated in 2023 is a more inclusive reflection of the wide-variety of circumstances in which someone may require fertility care services. See “Definition of Infertility: A Committee Opinion,” ASRM, 2023, https://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282(23)01971-4/fulltext.

2 Heba M. Eltoukhi et al., “The Health Disparities of Uterine Fibroids for African American Women: A Public Health Issue,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 210, no. 3 (August 11, 2013), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3874080/.

3 Gloria E. Anyalechi, “Tubal Factor Infertility, In Vitro Fertilization, and Racial Disparities: A Retrospective Cohort in Two US Clinics,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 48, no. 10 (October 1, 2021), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9012243/.

4 “Tubal Factor Infertility (Fallopian Tube Obstruction),” Columbia, accessed April 18, 2025, https://www.columbiadoctors.org/treatments-conditions/tubal-factor-infertility-fallopian-tube-obstruction; “Endometriosis and Infertility: Can Surgery Help?,” ASRM, modified 2023, https://www.reproductivefacts.org/news-and-publications/fact-sheets-and-infographics/endometriosis-does-it-cause-infertility/.

5 See e.g., Kristen Kreisel, “Prevalence of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Sexually Experienced Women of Reproductive Age — United States, 2013–2014,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66, no. 3 (January 27, 2017), https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6603a3.htm#:~:text=However%2C%20among%20women%20with%20no,%5D%2C%20p%20%3D%200.01 (“[A]mong women with no previous STI diagnosis, the prevalence of self-reported lifetime PID in black women was 2.2 times the prevalence in white women….”).

6 “Black Women and Endometriosis,” Resilient Sisterhood Project, accessed April 18, 2025, https://rsphealth.org/endometriosis/ (“A study by the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology reported that 40% Black women who were told they had PID actually had endometriosis.”); Nadine Dirks, “Misdiagnosis, Mistreatment, and Living with Endometriosis as a Black Woman,” MedicalNewsToday, July 24, 2020, https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/through-my-eyes-misdiagnosis-mistreatment-and-living-with-endometriosis-as-a-black-woman?utm_source=ReadNext.

7 See e.g., “The Endometriosis Resource Portal for People of Color,” Endometriosis Foundation of America, September 14, 2020, https://www.endofound.org/the-endometriosis-resource-portal-for-people-of-color; LV Farland and AW Horne, “Disparity in Endometriosis Diagnoses Between Racial/Ethnic Groups,” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 126, no. 9 (April 29, 2019), https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1471-0528.15805 (finding that Black women were less likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis than white women.); see generally Shannon Schumacher et al., “Five Facts About Black Women’s Experiences in Health Care,” Kaiser Family Foundation, May 7, 2024, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/five-facts-about-black-womens-experiences-in-health-care/#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20about%20one%20in,were%20refused%20pain%20medication%20they.

8 See “Environmental Justice and Reproductive Health,” Resilient Sisterhood Project, accessed April 18, 2025, https://rsphealth.org/environmental-justice/; “Clean Water and Reproductive Justice: Lack of Access Harms Women of Color,” National Partnership for Women & Families, July 2020, https://nationalpartnership.org/report/clean-water-and-reproductive-health/ (“High levels of lead exposure before and during pregnancy can also cause fertility problems, premature birth and miscarriage.”).

9 See Gloria Richard-Davis et al., “Caring for Black Women Seeking Fertility Treatment: Challenges, Stigma, and Hope,” ASRM, February 20, 2025, https://www.asrm.org/news-and-events/asrm-news/latest-news/caring-for-black-women-seeking-fertility-treatment-challenges-stigma-and-hope/ (“Conditions such as uterine fibroids, endometriosis, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)—all of which can contribute to infertility—are more prevalent among Black women. Yet, they are often diagnosed later in the disease progression, leading to reduced treatment options and lower success rates.”).

10 In 2018, over 69% of the 120,000 individuals of reproductive age diagnosed with cancer required fertility preservation procedures and services. “Fact Sheet: In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) Use Across the United States,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, March 13, 2024, archived content available at https://www.legistorm.com/stormfeed/view_rss/4436611/organization/69541/title/fact-sheet-in-vitro-fertilization-ivf-use-across-the-united-states.html. See also “Fertility for Transgender Women Before HRT: New Study Provides Answers,” Family Equality, accessed April 18, 2025, https://familyequality.org/resources/trans-fertility-new-study/ (highlighting the importance of fertility preservation services for transgender women).

11 Marissa Conrad and James Grifo, “How Much Does IVF Cost?,” Forbes, modified August 14, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/health/womens-health/how-much-does-ivf-cost/; “Costs of IVF,” FertilityIQ, accessed April 18, 2025, https://www.fertilityiq.com/fertilityiq/ivf-in-vitro-fertilization/costs-of-ivf#is-ivf-good-value.

12 See e.g., Julia Rothman and Shaina Feinberg, “What They Paid to Make a Baby (or 2),” New York Times, February 7, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/07/business/what-they-paid-to-make-a-baby-or-2.html?smtyp=cur&smid=tw-nythealth.

13 “Paying for Treatments: How Much Does Fertility Preservation Cost?,” Alliance for Fertility Preservation, accessed April 18, 2025, https://www.allianceforfertilitypreservation.org/paying-for-treatments/.

14 Courtney Anderson et al., “By the Numbers: Data on Key Programs for the Well-Being of Women, LGBTQIA+ People, and Their Families,” April 2024, https://nwlc.org/resource/by-the-numbers-data-on-key-programs-for-the-well-being-of-women-lgbtq-people-and-their-families/.

15 Michelle Andrews, “If You’re Poor, Fertility Treatment Can Be Out of Reach,” Kaiser Family Foundation, February 26, 2024, https://kffhealthnews.org/news/article/fertility-treatment-equity-obstacles/.

16 “The Wage Gap, State by State,” National Women’s Law Center, February 21, 2025, https://nwlc.org/resource/wage-gap-state-by-state/; “Gender and Racial Wealth Gaps and Why They Matter,” National Women’s Law Center, 2025, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/GENDER-AND-RACIAL-WEALTH-GAPS-Updated-2025-1.pdf; Ashir Coillberg, “A Window Into the Wage Gap: What’s Behind it and How to Close It,” National Women’s Law Center, February 26, 2025, https://nwlc.org/resource/wage-gap-explainer/.

17 Sarah Javaid and Kathryn Domina, “Women of Color, Disabled Women, and LGBT Adults Struggle to Afford Food and Housing Costs,” National Women’s Law Center, December 2023, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/nwlc_PulseWeek63FS-Accessible.pdf; Sarah Javaid, “The Persistent Housing and Food Crisis, Exacerbated by the COVID-19 Pandemic, Continues to Create Economic Insecurity Among Women and LGBT People of Color,” National Women’s Law Center, September 2022, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/HousingandFoodBrief22_accessible.pdf; Sarah Javaid and Melissa Boteach, “Child Care is Unaffordable in Every State,” National Women’s Law Center, February 2025, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Child-Care-Is-Unaffordable-in-Every-State-January-2025.pdf.

18 Heather Hahn and Margaret Simms, “Poverty Results from Structural Barriers, Not Personal Choices. Safety Net Programs Should Reflect That Fact,” Urban Institute, February 16, 2021, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/poverty-results-structural-barriers-not-personal-choices-safety-net-programs-should-reflect-fact; see also National Women’s Law Center, “Gender and Racial Wealth Gaps and Why They Matter,” at 1 (“Because of the preferential rates and loopholes available to the very wealthy, the current tax system (while progressive overall) enables enormous amounts of wealth to be accumulated by very few—who tend to be white and male.”).

19 See Ashir Coillberg, “Black Women Have Been Undervalued and Underpaid for Far Too Long,” National Women’s Law Center, March 2025, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/EPD-FS-2025-Black-3.18.25v2.pdf; Kyra Moeller, “Recent Report Highlights Economic Disparities for Black Women,” California Budget & Policy Center, February 11, 2025, https://calbudgetcenter.org/news/recent-report-highlights-economic-disparities-for-black-women/#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20Black%20women%20earned,single%20mothers%20earn%20just%20%240.56.

20 Drew Hawkins, “As Infertility Rates Rise, Data Shows Much of the US Lives in a ‘Fertility Desert’,” WBHM, August 8, 2023, https://wbhm.org/2023/as-infertility-rates-rise-data-shows-much-of-the-us-lives-in-a-fertility-desert/.

21 “The Wage Gap by State for Black Women,” National Women’s Law Center, February 21, 2025, https://nwlc.org/resource/wage-gap-state-black-women/; Melanie Campbell and Cassandra Welchlin, “We Need To Talk About How Southern Black Women Are Especially Harmed By Unequal Pay– And What We Can Do About It,” Essence, modified July 27, 2023, https://www.essence.com/news/southern-black-women-equal-pay-day/.

22 “Social Determinants of Health Metrics for Women, State by State,” National Women’s Law Center, May 4, 2023, https://nwlc.org/resource/health-metrics-for-women-state-by-state/; “Black Women Experience Pervasive Disparities in Access to Health Insurance,” National Partnership for Women & Families, April 2019, https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/black-womens-health-insurance-coverage.pdf (“Black women in the South have the lowest rates of health insurance coverage among all Black women.”).

23 Lexi Rummel, “When Women Are Deserted: The Prevalence and Intersection of Abortion Care Deserts, Pregnancy Care Deserts, Broadband Internet Deserts, and Food Deserts in the United States,” National Women’s Law Center, April 14, 2025, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Updated-Deserts-Report-1.pdf.

24 “Insurance Coverage by State,” RESOLVE, accessed April 18, 2025, https://resolve.org/learn/financial-resources-for-family-building/insurance-coverage/insurance-coverage-by-state/.

25 “Medicaid Coverage for Infertility Treatments and Fertility Preservation,” RESOLVE, accessed April 18, 2025, https://resolve.org/learn/financial-resources-for-family-building/insurance-coverage/medicaid-coverage-for-infertility-treatments-and-fertility-preservation/.

26 Donna L. Hoyert, Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2023 (National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2025), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2023/Estat-maternal-mortality.pdf.

27 Andreea A. Creanga et al., “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity: A Multistate Analysis, 2008-2010,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 210, no. 5 (May 2014), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24295922/ (“Non-Hispanic black…women had 2.1 times…higher rates of severe morbidity that were measured with blood transfusion compared with non-Hispanic white women….”); Sudeshna Mukherjee et al., “Risk of Miscarriage Among Black Women and White Women in a US Prospective Cohort Study,” American Journal of Epidemiology 177, no. 11 (April 4, 2013), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3664339/ (“Black women in our cohort were more likely than white women to experience a pregnancy loss. The increased risk was greater in the period from 10 to 20 weeks’ gestation.”); Tori B. Powell, “Black Women Are at Higher Risk for Miscarriage, Study Finds,” CBS News, April 29, 2021, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/miscarriage-risk-black-women/ (“Black women have a higher risk of pregnancy loss compared to White women, according to a study published this week in The Lancet, a peer-reviewed medical journal. Researchers in the United Kingdom analyzed data from 4.6 million pregnancies in seven countries, and the analysis suggests the risk is 43% higher for Black women.”); Shannon M. Pruitt et al., “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Fetal Deaths — United States, 2015–2017,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69, no. 37 (September 18, 2020), https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6937a1.htm#:~:text=Fetal%20deaths%20in%20the%20United,%2Dgestation%20pregnancy%20(2) (“[N]on-Hispanic Black (Black) women had more than twice the fetal mortality rate compared with non-Hispanic White (White) women and Hispanic women.”); Danielle M. Ely and Anne K. Driscoll, “Infant Mortality in the United States, 2022: Data From the Period Linked Birth/Infant Death File,” National Vital Statistics Reports 73, no. 5 (July 25, 2024), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr73/nvsr73-05.pdf (“Infants of Black non-Hispanic women had the highest mortality rate (10.90) in 2022….”). See generally Latoya Hill et al., “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them,” Kaiser Family Foundation, October 25, 2024, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/.

28 “Infertility Services: Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT),” Johns Hopkins Medicine, accessed April 18, 2025, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/gynecology-obstetrics/specialty-areas/fertility-center/infertility-services/preimplantation-genetic-testing#:~:text=Why%20is%20PGT%20helpful%3F,failed%20IVF%20cycle%20or%20miscarriage. Studies indicate that PGT may improve pregnancy outcomes for patients of advanced maternal age undergoing IVF treatment. See e.g., Laura Sacchi et al., “Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy Improves Clinical, Gestational, and Neonatal Outcomes in Advanced Maternal Age Patients Without Compromising Cumulative Live-Birth Rate,” Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 36, no. 12 (November 12, 2019), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6911117/#:~:text=PGT%2DA%20improves%20clinical%20outcomes,(CLBR)%20per%20egg%20retrieval. (“Crucially, pregnancy loss was significantly reduced in the PGT-A group, compared with all other comparative groups.”); Miguel Milán et al., “Redefining Advanced Maternal Age as an Indication for Preimplantation Genetic Screening,” Reproductive Biomedicine Online 21, no. 5 (November 2010), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20864410/ (“These results show that…reproductive success increases more than two-fold in patients over 40 years…suggesting a redefinition of advanced maternal age as indication for [preimplantation genetic screening].”).

29 “Costs of PGT-A,” FertilityIQ, accessed April 18, 2025, https://www.fertilityiq.com/fertilityiq/pgs-embryo-genetic-screening/costs-of-pgs.

30 See Rachel Gurevich, “How Much Does IVF Really Cost?,” Parents, July 25, 2024, https://www.parents.com/how-much-ivf-costs-8622386#toc-mini-ivf-vs-full-ivf; “Embryo Transfer: What It Is, What to Expect, The Different Types, and More,” CNY Fertility, modified November 21, 2024, https://www.cnyfertility.com/embryo-transfer/; “IVF Costs,” CCRM Fertility, accessed April 18, 2025, https://www.ccrmivf.com/ivf-cost/.

31 See “Guidance on the Limits to the Number of Embryos to Transfer: a Committee Opinion,” ASRM, 2021, https://www.asrm.org/practice-guidance/practice-committee-documents/guidance-on-the-limits-to-the-number-of-embryos-to-transfer-a—committee-opinion-2021/ (“Elective placement of multiple embryos is often influenced by financial considerations. Studies showed that insurance coverage for IVF was associated with the transfer of fewer embryos and with significantly lower rates of high-order multiple births. Financial pressures may be a coercive tipping point in favor of multiple embryo transfer.”).

32 Id. See also “Multiple Pregnancy: FAQs,” ACOG, modified January 2023, https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/multiple-pregnancy; “Complications of Multiple Pregnancy,” Johns Hopkins Medicine, accessed April 18, 2025, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/staying-healthy-during-pregnancy/complications-of-multiple-pregnancy.

33 Id.

34 In particular, older Black women undergoing fertility services have an amplified interest in the financial accessibility of genetic screenings, especially when considering the risks associated with pregnancy increase with age. See Donna L. Hoyert, Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2022 (National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2022/maternal-mortality-rates-2022.htm (“The [maternal mortality rate] for women age 40 and older was six times higher than the rate for women younger than age 25.”).

35 “Hidden Dangers of Miscarriages Scar Would-Be Moms,” NBC News, September 28, 2014, https://www.nbcnews.com/health/womens-health/hidden-dangers-miscarriages-scar-would-be-moms-n212646. Reducing the likelihood of miscarriage is also critical when considering that the criminalization of pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, like miscarriages, disproportionately harms Black people and people with fewer financial resources in long-lasting ways. See e.g., “South Carolina Pregnancy Criminalization Case Dropped in a Victory for Maternal Health,” Pregnancy Justice, September 11, 2024, https://www.pregnancyjusticeus.org/press/south-carolina-pregnancy-criminalization-case-dropped-in-a-victory-for-maternal-health/ (“Ms. Marsh, a respected member of her Orangeburg community, was a 22-year-old college student at the time of her miscarriage in March 2023. She was later arrested and charged with homicide by child abuse, which carries a sentence of 20 years to life — an extremely severe charge for the common experience of pregnancy loss. Although the outcome is positive in her case, this by no means erases the long-lasting harm that Ms. Marsh and her family experienced. ‘I’m relieved that my case is over, but they will never fully understand what they put me through. They interrogated me, charged me, arrested me, disrupted my education and turned my whole life upside down,’ said Ms. Marsh. ‘While facing a murder charge and the possibility of decades in prison, I still had to process my pregnancy loss. I’m now working to rebuild my life through counseling, and I’m back in school.’”); Julie Carr Smyth, “A Black Woman Was Criminally Charged After a Miscarriage. It Shows the Perils of Pregnancy Post-Roe,” AP, https://apnews.com/article/ohio-miscarriage-prosecution-brittany-watts-b8090abfb5994b8a23457b80cf3f27ce.

36 See generally Adetola Louis-Jacques, “What I’d Like Everyone to Know About Racism in Pregnancy Care,” ACOG, January 2024, https://www.acog.org/womens-health/experts-and-stories/the-latest/what-id-like-everyone-to-know-about-racism-in-pregnancy-care#:~:text=Racism%20in%20pregnancy%20care%20is,1%20in%205%20mothers%20overall; Yousra A. Mohamoud et al., “Vital Signs: Maternity Care Experiences — United States, April 2023,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 72, no. 35 (September 1, 2023), https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7235e1.htm.

37 See Lexi Rummel, “When Women Are Deserted” at 10 (“Nearly one quarter (23.7%) of all counties in the United States are both abortion care deserts and pregnancy care deserts, where over 2 million women of reproductive age live…Over 221,000 Black women of reproductive age…live in counties with abortion care deserts and pregnancy care deserts.”).

38 See e.g., Benjamin J. Peipert et al., “Impact of Comprehensive State Insurance Mandates on In Vitro Fertilization Utilization, Embryo Transfer Practices, and Outcomes in the United States,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 227, no. 1 (July 2022), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002937822001752 (“Comprehensive state mandated insurance coverage for in vitro fertilization is associated with greater utilization of these services, fewer frozen embryo transfers, and higher live birth rates.).