Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

The 19th Amendment Is Under Attack, and Not Every Woman Has an Equal Right to Vote

More than a century ago, after years of struggle and strife, suffragists won the right to vote for women. Every August, we mark the passage of the 19th Amendment with Women’s Equality Day. Yet, as our fundamental freedoms come increasingly under attack, it is important to ask:

Can we celebrate women’s equality when it has not yet been fully realized?

The victory for women’s suffrage was not as decisive as history might have us remember. It is true that, since 1920, the Constitution has prohibited U.S. citizens from being denied the right to vote based on sex. However, it is also true that, generations later, there are still women—particularly women of color—who are kept from participating in our democracy.

As we fight for a better future, there are three things we can learn from the past:

1. Beware of false choices.

“White supremacy will be strengthened, not weakened, by women’s suffrage.” These are words from Carrie Chapman Catt, a leading suffragist in her time. It is a hard and ugly truth that Catt was not alone in her convictions.

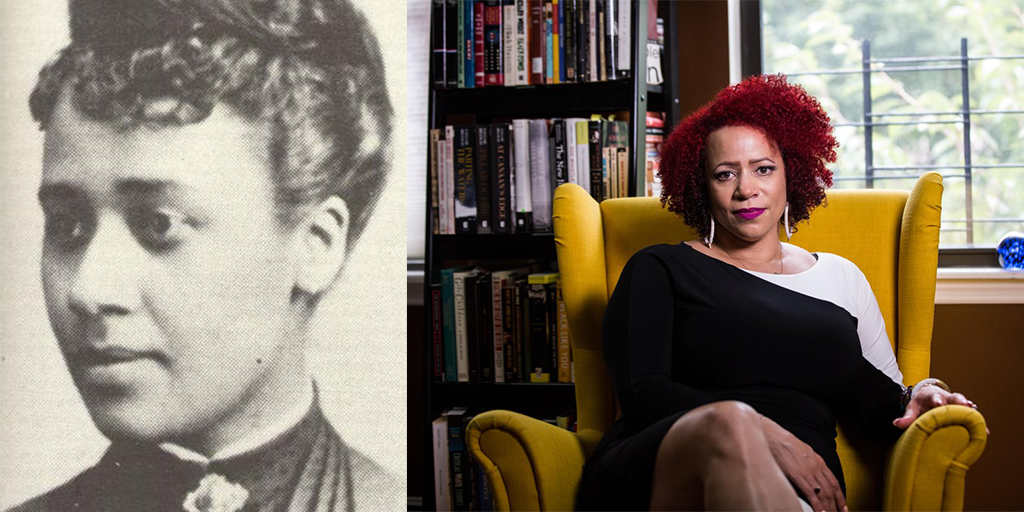

The movement for women’s suffrage was rife with racism. Black women were not invited to the gathering at Seneca Falls in 1848, and at the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade, organizers asked Black women to march in the back. Ida B. Wells, an icon of the civil rights and suffrage movement, refused this order, and instead, took her rightful place at the front with fellow movement leaders. (Coincidentally, she did so the same year Rosa Parks was born.) Following her example, other Black leaders of the movement did the same.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the 15th Amendment—which gave Black men the right to vote—was often pitted against the 19th. An icon of the women’s suffrage movement, Susan B. Anthony once said, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work for or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.”

Wells and others like Mary Church Terrell and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (who was recently portrayed in the star-studded TV series The Gilded Age) were leaders of both the civil rights and suffrage movements. They understood that Jim Crow voting restrictions were likely to supersede any voting rights women won, but they remained engaged nonetheless. They also called on white women to speak out—not just on suffrage, but on the violence being perpetrated against Black Americans. At one event, for example, Wells publicly challenged the views of Frances Willard, a white suffragist with racist inclinations, asking “how influential white women could continue to turn a blind eye to the white mobs who threatened Black lives.”.

The women’s suffrage movement reminds us to beware of the false choices that are presented to us. True freedom lives at the intersections, and the most successful movements are inclusive.

2. Equal rights mean little without equal access.

To the victor goes the spoils; yet, after securing the right of women to vote, not all women enjoyed that right.

Many Native Americans were not able to vote until 1924, and many Asian Americans were excluded until 1952. Meanwhile, after women won the right to vote, Jim Crow laws that prevented Black men from voting now extended to Black women, too.

A recent report from the National Women’s Law Center chronicles the years after women won the right to vote: “Prior to passage of the VRA, numerous states required fees called poll taxes in order to vote. This disproportionately suppressed Black voters because of existing social and economic racial disparities in the Jim Crow South, as well as women, who were often unable to work or access money without their spouse’s consent.”

For decades, poll taxes and literacy tests kept Black and brown women from the voting booth. Courts upheld these unconstitutional laws by allowing states to establish their own voting rules. Even into the mid-20th century, states continued using these mechanisms to prevent women and people of color from voting and building political power.

Much of the suffrage movement disbanded after the 19th Amendment was passed. In retrospect, it is clear: the amendment marked the beginning of progress, not the end. As President Lyndon B. Johnson said to Howard University’s Class of 1965, “It is not enough just to open the gates of opportunity. All our citizens must have the ability to walk through those gates.”

3. Celebrate victories, maintain vigilance.

Not long after he gave that speech, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law.

The landmark legislation—hard fought and hard won by a broad coalition of freedom fighters—addressed the discriminatory voting practices that many states put in place. For the first time, citizens could sue when their right to vote was being infringed upon. Plus, areas that had a history of discriminatory voting practices had to get approval before new voting laws could go into effect.

The impact of the Voting Rights Act was immediate. Our recent NWLC report explained that the law “helped to bring Black voters’ participation rates to near parity with other groups.”

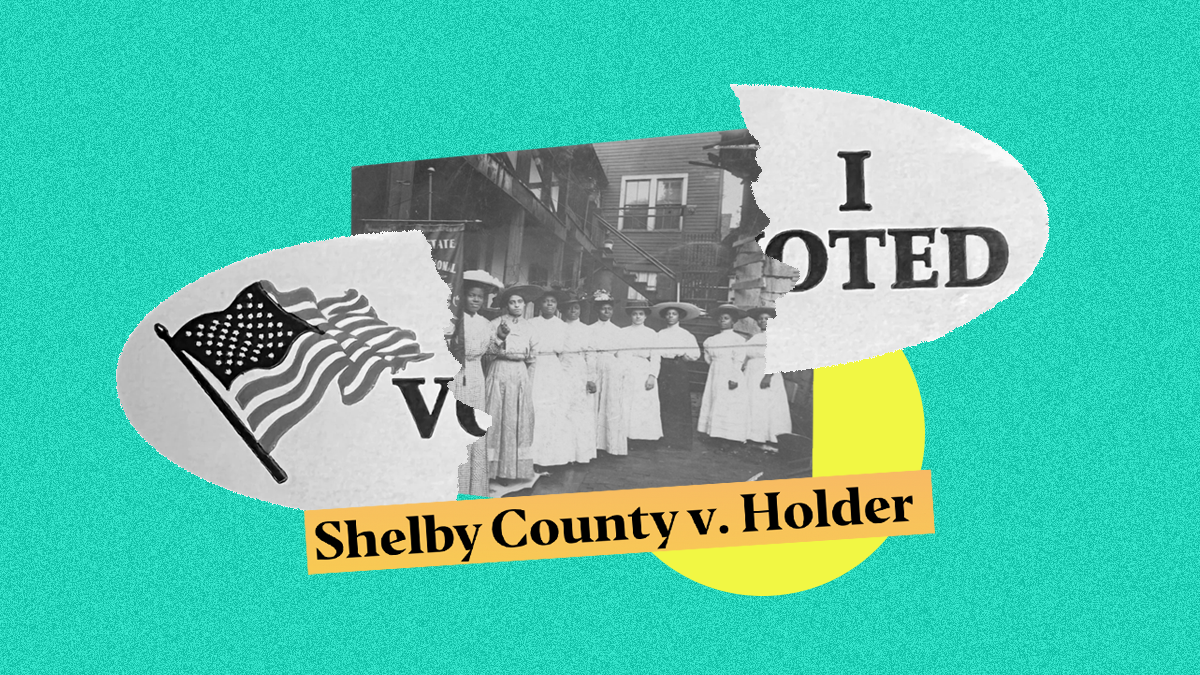

However, in 2013, that progress was interrupted when the Supreme Court decided Shelby County v. Holder. Key provisions of the Voting Rights Act, including the preclearance requirements—which require that any election legislation passed by certain states and localities that have a history of discriminatory practices be pre-approved by a court—were struck down. As a result, states like Texas, North Carolina, and Wisconsin moved quickly to establish new voter restrictions and resurrect gerrymandering efforts. Voter ID laws have become a barrier for people of color, LGBTQ+ people, low-income people, seniors, and students.

Since Shelby, fewer Americans are making their voices heard at the ballot box. In fact, the gap in turnout between Black and white voters has increased by 10 percent (from -2% to 8.3%). This disparity directly impacts our democracy. As our report notes, “A strong democracy that is responsive to the needs and votes of the people is crucial to protect the rights of women and families. Voters do not want abortion bans, cuts to schools and education, or cuts to social services that support women and families.”

It is no wonder, then, that the Trump administration has virtually abandoned enforcement of the Voting Rights Act. In addition, President Trump has issued an executive order to seize control of our election systems and has tasked federal agencies with targeting election officials. He has also sought to make it more difficult for immigrants to vote, and his Defense Secretary has praised a pastor who believes women should not be allowed to vote.

One hundred years since the passage of the 19th Amendment, our country has moved from gradually expanding the right to vote to reinstating voter suppression mechanisms and threats of disenfranchisement. Today, we must acknowledge the progress we have made— while remaining fiercely committed to the work ahead.

***

As we mark Women’s Equality Day, the question remains:

Can we celebrate women’s equality when it has not yet been realized?

The answer is yes. But only if we do our part to realize it.

There is so much we can learn from those who came before us about: How to build a movement and be an ally. How to win freedom and make it accessible. And, most of all, how to make progress stick by sticking together. History tells us that freedom is all or nothing. It takes all of us to win it, and we must win it for all of us. That is the way to a better future for everyone.

In 1898, Mary Church Terrell addressed the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association, later led by Carrie Chapman Catt. Terrell said then, “So, lifting as we climb, onward and upward we go, struggling and striving, and hoping that the buds and blossoms of our desires will burst forth into glorious fruition ere long.”

Onward and upward.