Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

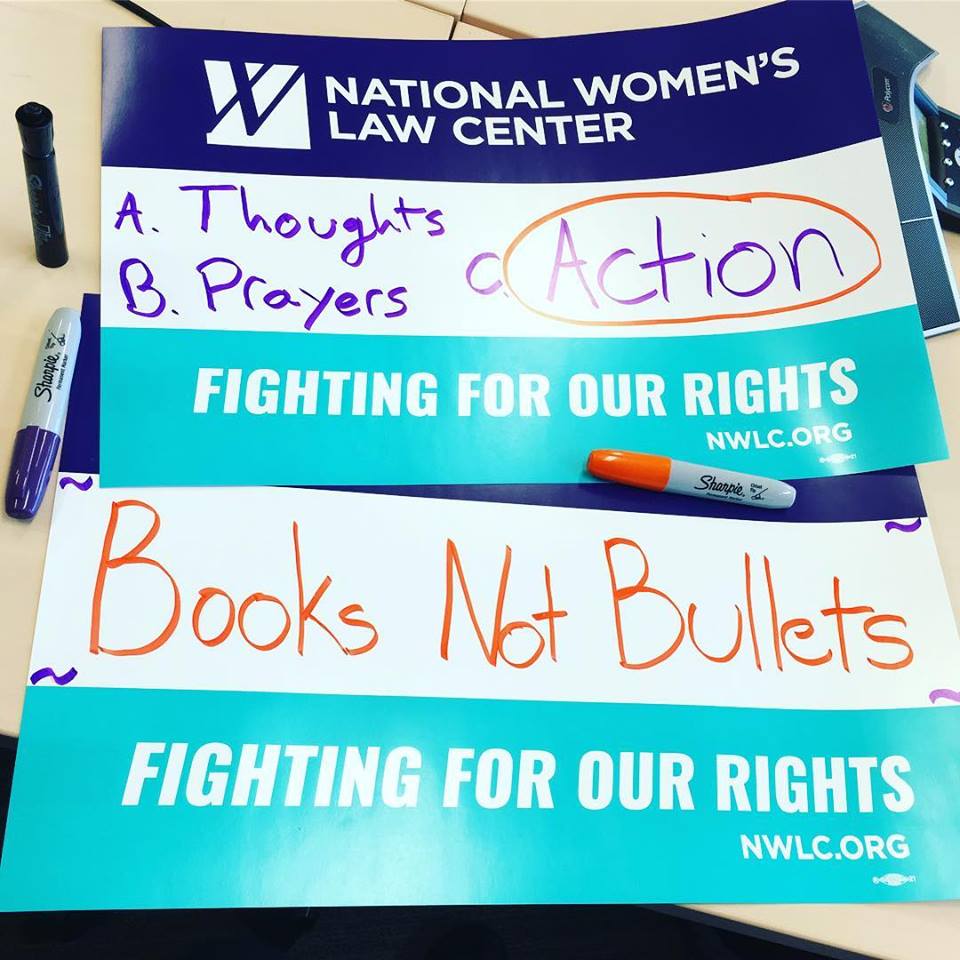

March for Their Lives: Of Course

“Thank you for marching for us.”

Somewhere between the ages of nine and twelve, curls pulled back in a loose ponytail and a smattering of freckles on pale brown cheeks, the young girl from my building met my gaze with quiet confidence.

Taken off-guard, I stumbled to respond.

—

Three friends and I had just walked into the elevator, on our way to breakfast and then the March for Our Lives, and had smiled and said hello to the two girls. The older girl had her arms draped over the shoulders of who I assume was her younger sister, squirming slightly with impatience in a bright pink t-shirt and wide eyes taking us all in. I recognized the eldest from the building but had never spoken to her before, aside, perhaps, from innocuous greetings during other elevator rides.

“Are you going to the March?” she asked. I hadn’t yet zipped my winter coat over my “Nasty Woman” t-shirt, and my friends and I had been chattering about sign-making. Giving her a wide smile, I said we were, and her little sister replied with something cute and precocious that I’ve since forgotten. Aside from a brief glance at the other women in my group, the older girl kept her eyes on me.

“Thank you for marching for us.”

—

The American education system can, in some ways, trace its history through the types of emergency drills being run in schools. Our social studies books show quaint-seeming black and white stills of nuclear bomb drills undertaken by plucky, clean-cut children in the third quarter of the last century. In the aftermath of 9/11, I vividly remember going through loosely defined “terrorist attack” drills twice a year at my middle school.

I was attending Singapore American School at the time, and the only real advice they gave us was to crouch under our desks or to find somewhere in the room that hid us from view of the windows. We were on the highest floor, barely able to see the sidewalks around the foliage even if we clambered up to peer through the glass. During one such drill, hands clasped around my uniform-clad knees, I stared skeptically up at the broad, green leaves of the flowering Angsana trees outside and wondered if our attackers would actually bother climbing them to get to us. I couldn’t really picture it; the attack, or how the teachers’ instructions would save us.

Both of those drills were designed to prepare for a shadowy sort of threat—something distant and intangible.

The threat facing American schools today is not vague. Students of all ages know exactly how these attacks sound and look—blood-smeared linoleum floors, small, unmoving bodies waiting for identification, bullet-splintered classroom doors. Images of exactly what kind of violence faces students have been splashed across our television, computer, and phone screens over and over again in recent months, weeks, days. They are so frequent now that the names and places have begun to blur horrifyingly together.

The mere fact of this frequency is unacceptable. Casualties in places of learning should be just as rare as the missiles feared in the heyday of the Cold War. Many people are now saying that all schools should implement “active shooter” drills. This shouldn’t be a conversation that we need to have.

—

During the March for Our Lives rally, 11-year-old Naomi Wadler said: “I am here to acknowledge and represent the African-American girls whose stories don’t make the front page of every national newspaper, whose stories don’t lead on the evening news.”

While I listened to her speak, I thought about my encounter with the girls in the elevator that morning, about the privileges my own white skin color grants me, for good or for ill. I thought about how the Trump-Pence administration’s ridiculous proposition to arm teachers would disproportionally negatively affect Black girls, who are often disciplined more than their white peers, despite there being no evidence of more frequent or serious misbehavior. I thought about all the dangerous distractions these children have to face daily while they’re supposed to be focused on growing up and learning, and the fact that such drills and looming threats can permanently scar people’s psyches. I thought about the lives that have already been stolen from us and about the witnesses who will never be the same.

Naomi’s eloquent speech was not the only moment when I thought of that elevator conversation, however. I carried that girl’s words with me during every step we took and every cheer I yelled. I will continue to carry her with me during every day I work here at the Law Center and through all days of activism in the future. Not just regarding supporting more comprehensive gun control and keeping schools from being turned into prisons, but for all causes—those girls are the future, and the future is what I’m fighting for.

—

“Thank you for marching for us.”

“Of course,” I stuttered through a shaky smile, voice a bit thicker than it had been before.

Of course I will march for her, for them. We will carry the thought of them with us until the day that we don’t need marches like this anymore.