Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

Chinese Food for Thought

I’ve always had a complicated relationship with food. Food and cooking were how my family showed love and built community. It was part of my cultural heritage. A point of pride. A regular greeting at my household was: “Have you eaten yet?” Meals were really the only time my family would sit and have conversations about school and my day. While food in the home was a symbol of togetherness, to me, Chinese food in society represented feelings of isolation, shame, and otherness.

Growing up, my immigrant parents owned a Chinese restaurant in a primarily white neighborhood. But, I always secretly resented that place. I resented that my parents had to labor long hours in a dingy, greasy restaurant and never had time for us. I hated that I had to work there on the weekends and holidays and be forced to smile at guests who would tell me “wow, your English is so good.” I resented the snide remarks from kids who claimed that I “smelled like Chinese food” or that “Chinese food is cheap and gross.” I also felt a lot of shame about the fact that my parents and extended family worked in restaurants.

The U.S. is home to over 40,000 Chinese restaurants. While American Chinese food is a central part of the mainstream American cuisine, the prevalence of the Chinese food industry stems from a storied history of anti-Chinese sentiment. Chinese workers began migrating to the United States in the 1850s during the height of the railroad boom, primarily working in mining, agricultural, factory, and garment industries. Rampant racism and resentment toward Chinese immigrants – along with the fear that they would depress wages and take away jobs from Americans – led Congress to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which blocked all immigrants from China and prevented Chinese immigrants already in the country from becoming citizens.

There was an exception to these xenophobic laws: Chinese business owners could get special merchant visas to travel to China and bring back employees, and restaurants were included in the list. While this loophole allowed some Chinese immigrants to enter the country, the visa was only granted to investors of “high grade” fancy eateries who exclusively managed the restaurant, and it required two white witnesses to support the petition. Often, workers would pool their money to start “Choy Suey” restaurants and then bring over relatives to work at their restaurants who then moved up in the hierarchy and eventually started their own restaurants. Because this was one of the only means for Chinese immigrants to come to this country, working at a restaurant was a central part of many Chinese American immigrant stories in this country.

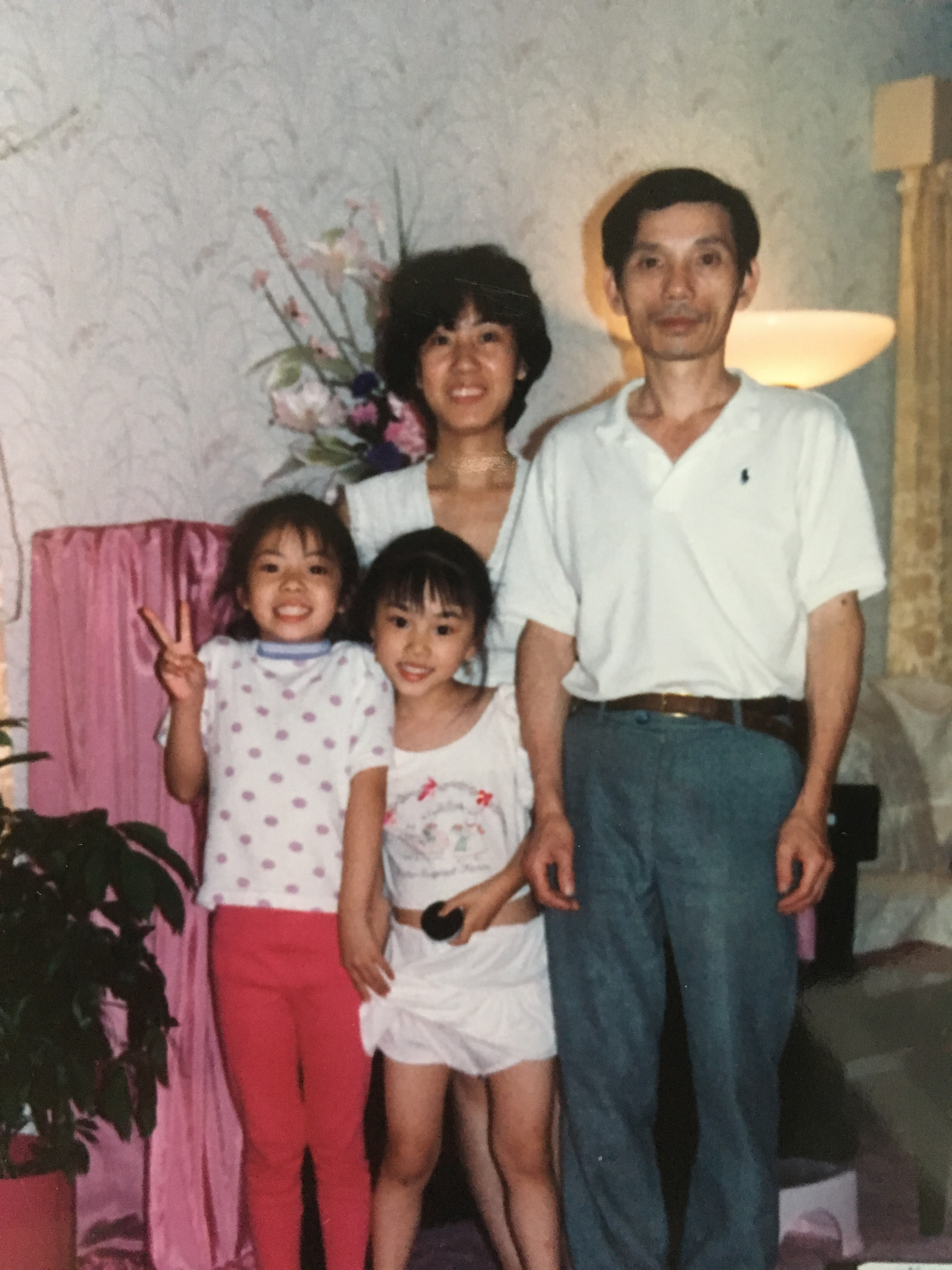

My father’s immigrant story fits neatly in this narrative. He grew up in a poor farming village in Canton China during the Cultural Revolution. He fled Mainland China as a refugee, making his way to Hong Kong, and eventually the United States. After my dad immigrated to this country in the 1970s, he worked at various Chinese restaurants, saving enough money to send home and eventually bring his family to the United States. To him, the American Dream was about working hard, gaining stability, and giving opportunities to your children that you never had. It’s the same dream that many immigrants today have when they take the risk to come to this country.

While people often lament how much the immigration system has changed, the reality is that anti-immigrant sentiment is deeply ingrained in our history. The demonization of immigrants and perpetuation of the false good/bad immigrant narrative is not new. However, white nationalist groups are further emboldened by Trump and his administration’s hateful agenda to spread their extreme anti-immigrant fervor. The cruel and inhumane detention of immigrants at the border is yet another despicable stain on our history. While immigrant heritage month is about celebrating immigrant stories and our diverse cultural traditions, we also should not and cannot ignore the past and present injustices faced by immigrant communities.

While cooking and eating food from my motherland brings me so much joy on a personal level and is my way of honoring my family’s traditions, I remain extremely protective of my culture’s food. I’m often torn about how mainstream Asian food is becoming. I am particularly irritated by “trendy Asian food” or “clean Chinese food” that sanitizes traditional cooking to be more palatable for the masses. The history of Chinese food and the discrimination faced by those in the industry is deeply personal to me and to everyone who lived this shared experience. Food has been a source of resilience and resistance for my community. I am no longer resentful or ashamed of the role food and the restaurant industry played in my life. I am reclaiming and honoring that experience. It’s a key piece of my immigrant story. It’s a part of my Asian-American identity.