Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

If at First You Don’t Succeed . . . Try an Executive Order That Allows Health Insurance Companies to Discriminate Against Women

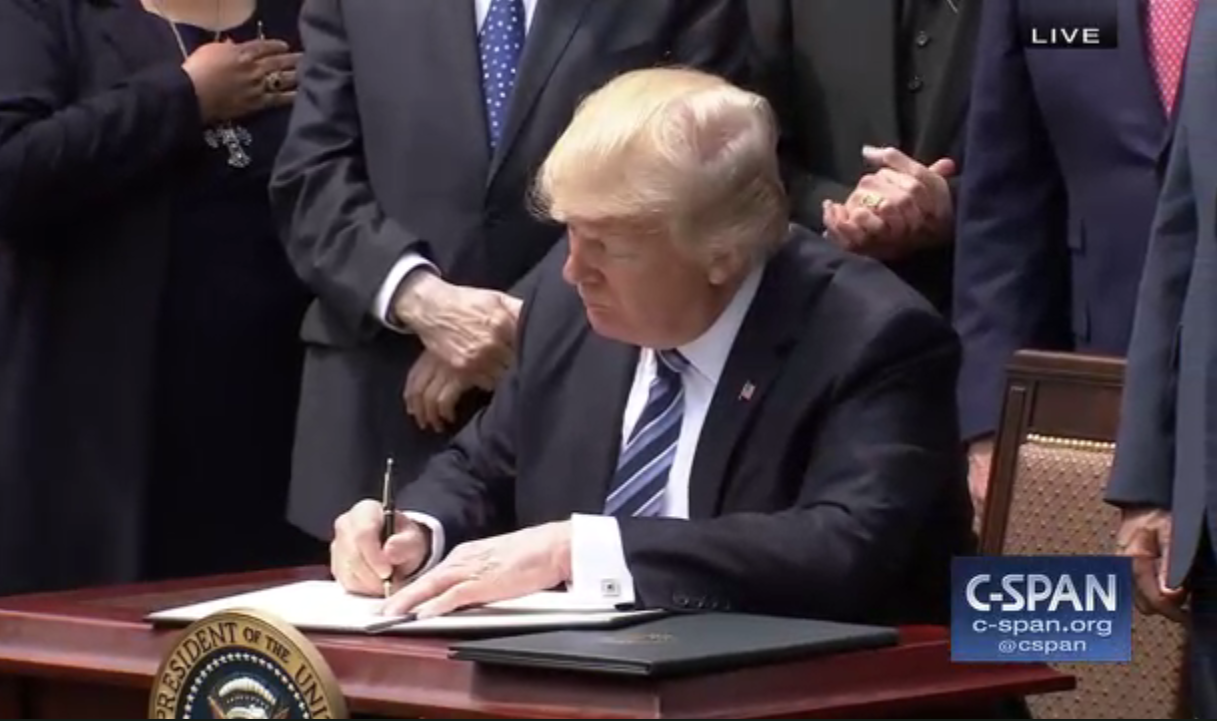

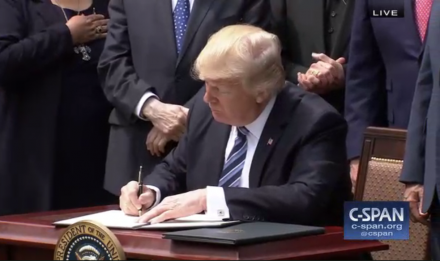

After conceding defeat of congressional attempts to dismantle the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Trump Administration is now using executive action to try to undermine and gut the law. Today, the Administration issued an executive order (EO) directing the Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, and Treasury, to figure out ways to allow insurers to undermine the ACA. In particular, the EO asks the departments to reexamine rules to extend the duration of short-term plans from a three-month maximum to up to a year and permit the sale of association health plans. Many short-term and association plans generally do not include the ACA’s consumer protections.

After conceding defeat of congressional attempts to dismantle the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Trump Administration is now using executive action to try to undermine and gut the law. Today, the Administration issued an executive order (EO) directing the Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, and Treasury, to figure out ways to allow insurers to undermine the ACA. In particular, the EO asks the departments to reexamine rules to extend the duration of short-term plans from a three-month maximum to up to a year and permit the sale of association health plans. Many short-term and association plans generally do not include the ACA’s consumer protections.

The bottom line is that today’s EO is bad for women – it jeopardizes access to health coverage for the more than 89.6 million women ages 18-64 nationwide who—thanks largely in part to the ACA—now have health insurance coverage. Do not be fooled—today’s EO is not about consumer choice or more coverage options, it is a politically calculated attack on the ACA.

So, why is this EO bad for women’s health?

Because women have benefitted from key ACA consumer protections like prohibitions against discriminating against people with pre-existing conditions and requirements that plans cover basic health services, like preventive care. The EO would allow insurers to return to pre-ACA discriminatory practices that harmed women and limited their access to health coverage.

So, here’s the rundown of some of the key ways today’s EO would allow insurers to harm women’s health:

- The EO tasks the departments with extending short-term plans, previously limited to three months in duration under the Obama Administration, to up to one year. Short-term coverage is intended as stop-gap coverage. For example, one might purchase short-term coverage while in between jobs. Extending these plans to offer coverage up to one year could have devastating effects for women who rely on such plans as their primary sources of care. Here’s why:

- Short-term plans are notorious for offering skimpy coverage that does not meet most of women’s health needs, like maternity care, prescription drugs, or mental health services. Coverage of these services is vital not only for ensuring that women’s health needs are met, but also for promoting women’s economic security. Without coverage requirements for these key services, women are left paying out-of-pocket for the care that they need—and these costs can be significant. For example, maternity costs for women can range from over $30,000 to more than $50,000 for more complicated births. And birth control costs can range up to $1,000 for more effective longer-acting forms. Compound these costs with out-of-pocket costs for mental health services, substance abuse and rehabilitation services, and other prescription costs—all of which short-term plans are not required to cover—and even the healthiest of women will be left shouldering high out-of-pocket costs.

- The EO also allows short-term plan issuers to discriminate against those with pre-existing conditions. This means that many short-term plan issuers will once again—as they did pre-ACA—be able to deny coverage to the over 65 million women nationwide with pre-existing conditions. Prior to the ACA, women were disproportionately impacted by denials of coverage based on pre-existing health conditions that were specific only to women, like prior pregnancies. By prohibiting insurers from denying coverage or charging more for those with pre-existing conditions, the ACA helped to ensure that women with pre-existing conditions had access to quality and affordable coverage. But, since this EO allows issuers to consider health status when making coverage decisions, it is very likely that only healthy people will be able to enroll in short-term plans. This will pull healthy people off the ACA’s health insurance marketplaces, as they opt for cheaper and skimpier short-term plans, leaving sicker individuals on exchanges. Exchanges with individuals with more health needs, means higher costs, as those with more health needs are more expensive to cover. Therefore, this EO will have repercussions for the economic security of those remaining on ACA marketplaces.

- But, what the healthy consumers who opt for skimpy short-term plans may not know is that they will be left without the ACA’s financial protections in case of a medical emergency because short-term plans are not required to limit cost-sharing . This could upend economic security for women in short-term plans, as high costs can drive individuals and families into bankruptcy—which happened frequently pre-ACA.

- The EO also tasks the departments with figuring out how to permit the sale of association health plans, which often do not offer robust health coverage that helps to meet women’s health needs. While these plans may initially seem attractive for small businesses seeking to group together to offer coverage, experience shows that such plans don’t result in strong coverage or consumer protections. States, like Washington, that have tried to sell association health plans know they don’t work—Washington’s own Insurance Commissioner notes: “Association health plans often shun the bad risks and stay with the good risks.” This means that those with significant health needs would likely not be able to secure the coverage that meets their needs under these plans. And, leaving women without coverage for the health services that they need means high out-of-pocket costs, which are especially burdensome for women struggling to make ends meet.

We simply cannot return to a time when discrimination was commonplace on the health insurance market. The ACA’s protections have changed the landscape for women’s access to health care and coverage, particularly women struggling to make ends meet, women of color, and LGBTQ individuals who experienced widespread discrimination in the health sector prior to its passage. We must continue to resist this and other heartless attacks on vital health coverage and services for women.