Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

Discrimination Against Disabled Asian American Women Is Rooted in Our Flawed History

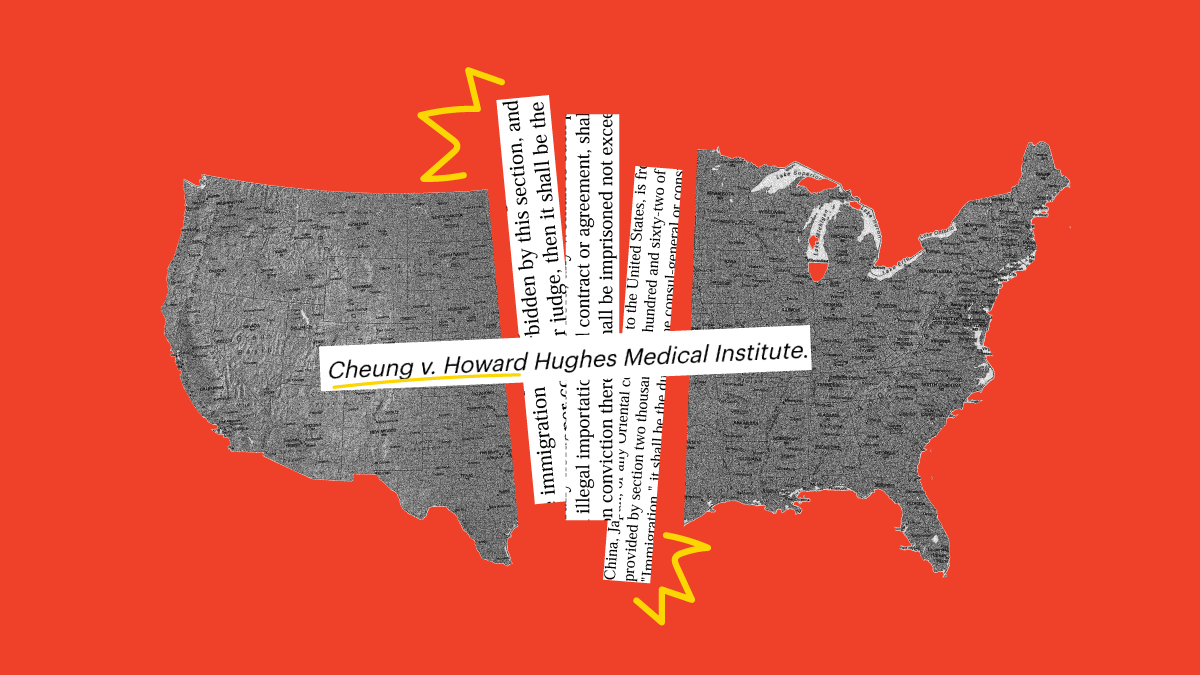

Last week, the National Women’s Law Center filed an amicus brief supporting Dr. Vivian Cheung in her ongoing lawsuit against Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI).

Dr. Cheung is a pediatric neurologist and molecular biologist responsible for cutting-edge findings around the genetics of complex medical conditions. For me, an Asian American woman, it is very, very cool to see an Asian American woman being a leader in her field.

Ten years ago, in a twist of irony, Dr. Cheung discovered she had a genetic disorder so rare it didn’t even have a name. And then HHMI, her employer, declined to renew her multimillion-dollar research funding. Believing that HHMI’s decision had more to do with her race, gender, national origin, and disability than with her work, she sued HHMI for discrimination in Maryland state court. Last year, the state court allowed her disability discrimination claim to move forward but dismissed her other discrimination claims.

Our brief argues that when a person holds multiple marginalized identities, they experience distinct harms that cannot be understood by viewing each aspect of their identity in isolation. To help the court understand how Dr. Cheung’s identities intersect, we discuss our country’s shameful past and present discrimination against Asian American women and how it interacts with disability and ableism.

The first wave of Asian migration to the United States in the 1800s occurred because the country needed cheap labor after the end of slavery. Then once they didn’t need us anymore, they barred us from entering the country.

And U.S. history is even more shameful when it comes to Asian women. The Page Act of 1875 effectively prohibited women from “China, Japan, or any other Oriental country” on the premise that they were “seeking entry for lewd or immoral purposes.” Then in the mid-1900s, U.S. military involvement in Asia, the sex tourism industry that followed, and the fact that the Asians who were allowed into the country were predominantly women married to American soldiers reinforced the view that Asian American women existed only for the comfort and gratification of men.

Today, Asian American women in workplaces often confront multiple, contradictory stereotypes. Employers and coworkers expect them to fit the mold of servile “lotus blossoms” or fierce “dragon ladies,” while at the same time being high-achieving members of a “model minority” who don’t make waves. But conforming to these stereotypes ultimately hinders Asian American women from getting ahead in the workplace: they are more likely to be overlooked for promotions or perceived as overly aggressive. In short, we can’t win.

While it might seem benign at first, the model minority myth is insidious. It stereotypes Asian Americans as naturally successful to downplay the impact of discrimination against all people of color. It also erases the hundreds of ethnicities that exist within Asian Americans, conflates Asian Americans with Asians, and flattens all of them into a single stereotype of a compliant high achiever. For disabled Asian Americans like Dr. Cheung, the myth can also cause employers to downplay their disability-related needs and judge their work more harshly when they fail to “live up” to inflated expectations.

If any of this sounds unfamiliar, you are not alone. Most U.S. history curricula brush over Asian American history. The only instance of Asian American history I can remember being taught before college was about the Japanese American internment camps during World War II, before we quickly pivoted to D-Day.

Would the court have allowed Dr. Cheung’s other claims go forward if more of us knew our Asian American history and its lingering effects into the present? Would HHMI have decided not to yank its funding for Dr. Cheung’s research? I don’t know. But I do know that I would have been less likely to hear friends say things like, “Well, Asians are basically white” or “You guys have taken over our schools.”

As I was working on this brief, I had just finished reading “On Juneteenth by historian and law professor Annette Gordon-Reed, who tells us that origin stories “inform our sense of self; telling us what kind of people we believe we are, what kind of nation we believe we live in.”

What if the origin stories of an entire group of people are not told or told wrong? What does that tell us about who we are, the country we think we live in, and the value society places on that group?

In recent years, some states have begun requiring schools to teach Asian American history, which makes sense because Asian American history is American history. And while we wait for the students now learning this history to eventually join the workforce, I hope we can foster not just workplaces but a larger society that both empowers and respects Asian Americans.