We Deserve Better: Breaking Down Educational Barriers for Girls with Disabilities

“She won’t get in to high school if this continues.” “Are you even trying?” “C’mon on just focus, this isn’t hard stuff!”, “College just isn’t for everyone.” These are the lines girls with disabilities are confronted with time and time again throughout our lives. An expectation that less should be expected of us or that we should just try harder. And many of us don’t realize it’s wrong. We are often treated as if the behavior we can’t control, the way we understand the world, the accommodations we need are a burden on educational spaces. We don’t deserve to be treated this way, yet we accept this treatment because the lived experiences of girls with disabilities aren’t discussed or acknowledged. To be honest, I couldn’t identify these problems until I read NWLC’s Stopping School Pushout for Girls with Disabilities. Disseminating this information in the report is vital for girls. It lays out how girls with disabilities and our allies can push back against a status quo that, quite frankly, keeps us from achieving our full potential.

Lack of support and the danger of being unseen

While schools have a legal obligation to provide equal opportunity to all students—including students with disabilities— that promise is often unfulfilled. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires that a free, appropriate public education must be provided to eligible students with disabilities. IDEA requires all public schools to file an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) for every student with a disability who meets federal and state requirements. While the act itself says all the right things, according to the findings from NWLC, the way schools implement the law doesn’t meet expectations, especially in the case of girls with disabilities. While there are around the same number of girls with disabilities as boys, boys are two times as likely to be identified under IDEA and receive support. The discrepancy is particularly high for some disabilities. For example, five and a half times as many boys as girls are identified as having autism. While it is unclear why exactly this is the case, one explanation could be differences in the way disabilities express themselves. While girls may show clear signs of a disability from an early age, such as slower processing time, being nonverbal, compulsive behaviors or having difficulties with fine motor skills, it may be that girls do not outwardly disrupt class with their behavior. This results in insufficient attention for girls with disabilities and a perception that they are not “priority.”

Inadequate accommodation & the effects of isolation

It is common practice for schools to coerce students into an IEP that mandates that a student be taken out of class, often this is the only “assistance” provided. But in my experience, this leads to isolation for girls with IEPs for a few reasons. For one, because girls with disabilities are less likely to have their disabilities identified, they are often . This approach fosters a lack of attention and fails to provide engaging instructional approaches for all students, especially girls. Research shows in school, which includes being placed in a room alone without being allowed to leave. In addition to otherizing girls, seclusion practices exacerbate feelings of anxiety and depression already felt by many students with disabilities and causes them to withdraw even further.

Higher rates of Absenteeism

According to NWLC’s research, girls with disabilities have high rates of absenteeism. This is due, in part, to things like doctor or hospital visits, CT scans, physical therapy or psychiatric appointments. Additionally, other health issues related to disability, such as broken bones, partial paralysis, heart or breathing difficulties, chronic fatigue, migraines or equilibrium issues can keep girls with disabilities out of school.

But what many students with disabilities know and experience is that these high rates are also caused by girls feeling unaccommodated by their school . For example, due to my disability, at one point in elementary school, I had to use crutches because I broke both of my ankles. My regular classroom was located on the third floor, but my school did not have an elevator or any way for me to get up the stairs. My school’s solution was to assign me to the special education classroom on the first floor. Not only did this mean that I was unable to participate in my regular classes, but it meant trying to complete course work on my own in a loud class (which aggravated my sensory sensitivity to sound) with a completely different program. Eventually, I found myself asking my mom to call in sick or wanting to skip school to stay home and work rather than be in that environment. As the NWLC Report shows my experience is not uncommon and schools’ failure to properly accommodate girls with disabilities pushes us out of school.

What can we do?

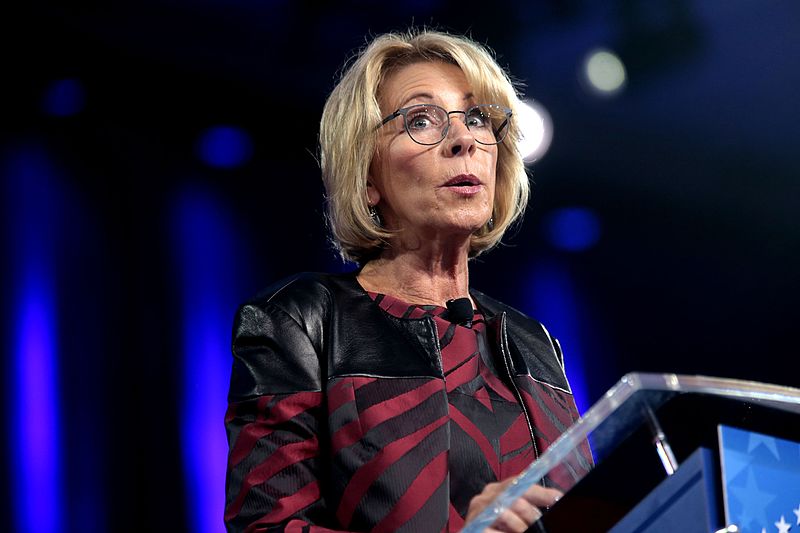

Our Report found that policymakers, schools and parents all have a part to play. Especially in light of the incredible disregard shown by Betsy DeVos’ “leadership” of the U.S. Department of Education and the continued attacks on protections for students with disabilities, our report offers suggestions of how to appeal to your representatives. After all, at the end of the day they work for YOU. Schools can also help by taking initiative in training teachers on how to identify and assist students with disabilities as well as implementing IEPs properly. Additionally, schools must start by listening to what girls with disabilities have to say about what they would like to see done—they’re the experts after all. Lastly, parents can support their children by helping girls understand what they’re entitled to under the law and empowering their child to advocate for herself.

The feeling I had throughout my education, of continuously running after a train that could never be reached, didn’t have to be that way. Not every student with a disability does poorly in school. Rather, if the expectation is that one will never amount to anything, at some point, Girls may absorb and believe that false message. Girls shouldn’t have to demand attention to receive the support we need. This is not asking for much, just the chance to receive the equal opportunity for an education, to receive the accommodations we need, to have our schools and our policymakers do better.