Introduction

Child care is an essential element of our social infrastructure and economic stability. It supports the healthy development of children, helps families achieve financial stability, and keeps the economy running. Yet, the child care sector is only as strong as the early educators and providers that make up the workforce and who care for children across a range of settings. Early educators are predominantly women (94 percent) and more specifically women of color—Black early educators and Latina early educators make up 12 percent and 21 percent of early educators respectively,1 and importantly, 22 percent of early educators are immigrant women (compared to just 8 percent of the overall workforce).2 Despite being the backbone of our child care system, child care workers are underpaid and undervalued, and harsh anti-immigrant policies threaten to further destabilize a precarious workforce supply and raise already high child care costs for families by pushing immigrant workers out of or away from care work.

Immigrant early educators are a critical pillar of the child care workforce and meet the unique needs of rapidly diversifying younger generations and their families. Yet, immigrant early educators face additional barriers to entering and staying in early childhood education (ECE) for a variety of reasons, including the impacts of anti-immigrant policies and rhetoric. As the ECE field continues important advocacy to support early educators to achieve fair wages and access to benefits, it will be critical to ensure that immigrant child care educators and providers are not left out of the conversation. Without the experience and expertise immigrant early educators bring to the field, the child care sector could face significant structural damage that would be difficult to recover from. ECE champions and advocates must recognize and elevate immigration as a core issue within early childhood education, understanding that harsh immigration policies will directly impact children, families, and early educators.

What we know about immigrant early educators

1. Immigrants are a significant portion of the child care workforce.

Immigrants compose a significant part of the early childhood care labor force, currently making up about 20 percent of early educators, up from 5 percent in 1980.3 According to analysis by the Economic Policy Institute, 9.8 percent of child care workers are women who are naturalized citizens, and 10.9 percent are women classified as “non-citizens,”4 which EPI defines as being permanent residents, undocumented immigrants, or temporary migrant workers employed through “nonimmigrant” visas. Based on available data, the largest share of immigrant early childhood educators work as center-based child care workers as center-based child care workers (26 percent), followed by preschool teachers (23 percent), family-based child care workers (21 percent), private home-based child care workers (20 percent), teachers assistants (7 percent), and program directors (3 percent).5 However, it is important to recognize that it is likely that a large share of immigrant child care providers are operating as Family, Friend, and Neighbor (FFN) providers who are not reflected in this data, both due to data limitations and citizenship status.

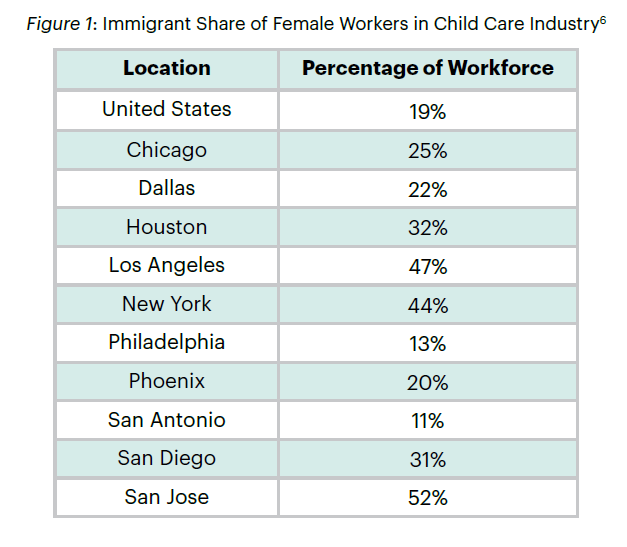

2. Immigrant women are integral to the child care workforce nationally and regionally.

A 2022 study also found that immigrant women were a significant percentage of the child care workforce across the country.

3. Immigrant early educators are well-educated and pursue professional development.

Studies have found that among lead teachers in center-based child care programs, 64 percent of immigrant early educators have an associate or bachelor’s degree, compared to 53 percent of nonimmigrant early educators.7 U.S. Census Bureau data also show a marked increase in the share of newer arrivals with more advanced education credentials. Between 2020 and 2022, for example, 48 percent of immigrants who entered the country held at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to 34 percent of recent arrivals as of 2000.8 Additionally, immigrant early educators are more likely to have professional credentials like the Child Development Associate (CDA) and invest in more professional development events every month.9 Despite this, immigrant early educators are paid a median income of $11.54 an

hour10—this is compared to the median hourly wage of $14.56 for all child care early educators.11

4. Immigrant early educators are more likely to be Latinx12 and are bilingual or multilingual.

Today, over 90 percent of early educators are women, and women of every race and ethnicity are overrepresented in ECE. As of 2021, Latinas make up 21 percent of early educators, compared to 8 percent of workers in all sectors.13 Early educators are also linguistically diverse, with more than a quarter (27 percent) of center-based early educators speaking a language other than English. For home-based providers, that number is 32 percent for listed providers and 35 percent for unlisted providers.14 Cultural knowledge combined with language skills are critical assets for serving the needs of rapidly diversifying younger generations and their families—currently, a quarter of young children under 5 are families with at least one parent who is an immigrant.15

What Child Care Advocates Need to Know About Immigration Policy

As noted, immigrant early educators play a critical role in children’s healthy development and strong family engagement, and serve as a crucial workforce supply pillar in a sector that struggles to attract and retain workers due to chronic low pay and lack of benefits. As such, it is important to understand any effort that deters immigrant early educators from entering or remaining in the ECE field. In particular, changes in immigration policy, particularly harsh anti-immigrant measures as seen in the current Trump administration, could present a significant challenge to the early childhood education sector.

First, the administration has been clear that their goal is to detain and deport as many people as possible without regard for humanity, the law, or an individual’s lawfully present immigration status.16 Trump is doing so by executive actions, which terminate temporary statuses that protect individuals from deportation,17 expand the grounds for deporting individuals,18 and rescind long-standing policy limiting immigration and customs

enforcement (ICE) efforts in places designated as sensitive locations such as schools, hospitals, places of worship, and child care centers, among others.19

Second, Trump has sought to restrict immigrants’ access to public benefits and services particularly through an executive order titled “Ending Taxpayer Subsidization of Open Borders.”20 Importantly, undocumented immigrants are already not eligible for federally funded programs,21 despite contributing greatly to the revenue sources that uphold the care economy. As both consumers and taxpayers, immigrants added $2 trillion to the U.S. GDP in 201622 and $458.7 billion to state, local, and federal taxes in 2018, with undocumented immigrants contributing $11.4 billion in taxes that same year.23 For so many immigrants and their families, this means paying into systems of public support that they are not able to benefit from.

More targeted attacks on immigrant and mixed-status families are expected from this administration, including continued threats to birthright citizenship, which if successful would have devastating consequences on young children’s ability to access critical benefits from birth.24

Given that immigrants are a significant population in the ECE labor market, changes in immigration enforcement policy can impact their entry into this sector. A 2022 study assessed the impact of the Secure Communities (SC) Program, an immigration enforcement effort25 that expanded immigrant deportations. The study found that between 2008 and 2014, the SC initiative deterred 8.6 percent of immigrant workers from entering the child care sector, driven by 15.8 percent fewer Latina immigrants entering into ECE roles.26 Given the administration’s efforts to deport as many undocumented individuals as possible, the ECE labor market may see similar trends in the future.

The ECE sector is already feeling the chilling effects of heightened uncertainty due to these policy changes. These policies not only impact immigrant families27 but also exacerbate challenges for the ECE workforce. Concerns about the future of programs like Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA),28 visa renewals, and the rescission of the sensitive locations policy create additional barriers for current and prospective ECE educators, further straining a sector already grappling with severe workforce shortages.29 The shortage of culturally and linguistically responsive early educators is even more acute, and anti-immigrant policies threaten to deepen that gap, making it even harder to meet the diverse needs of children and families.