Our Child Care System Relies on the Labor of Immigrants—But Immigrant Families Can’t Rely on the Child Care System to Work for Them

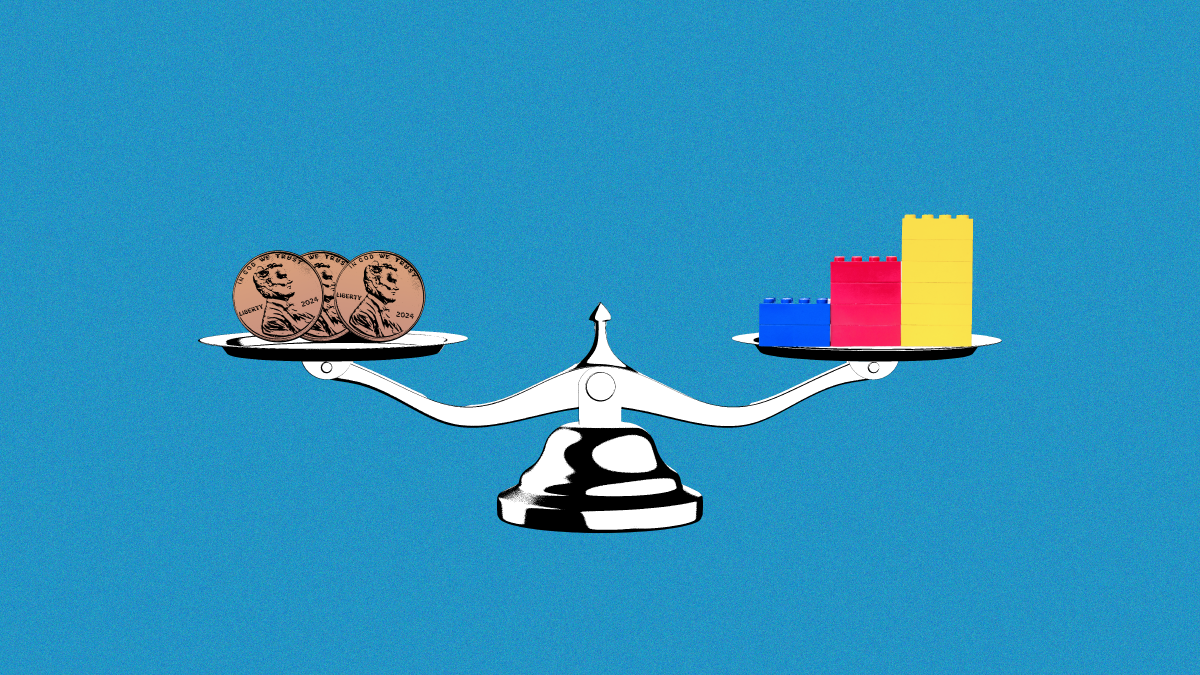

As of 2021, foreign-born women made up 22% of all child care workers in this country, compared to just 8% of workers in all sectors. In other words, immigrants hold up our child care system—yet too often, they cannot find, access, or afford quality child care for their own children.

There is no quick fix to the many injustices and inequities that immigrant families face in this country. There are, however, tangible steps we can take to make sure that immigrant families are better served in our child care system:

- Increase child care workers’ compensation.

First and foremost, an early childhood education and care system that was set up to support immigrant families would recognize the vital work immigrant providers do by paying them fair wages, instead of the mere $14.60 median hourly wage that full-time, year-round child care workers were making as of 2023. The early care and education workforce, including those who are immigrant workers, should receive health care, paid leave, and other benefits as well.

- Increase the affordability and accessibility of child care.

Despite the workers’ low wages, child care in this country is unaffordable for most families. In 2022, the national average annual price of child care was equal to 10% of the national median income for married couples with children and 33% of the national median income for single parents. Both of these percentages far exceed the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ benchmark for affordability for child care. Many immigrants, one-third of whom had low-incomes in 2019, find it particularly difficult to afford child care.

While some federally and state-funded child care programs for low-income communities are available regardless of the child’s immigration status, lack of clarity around eligibility rules and restrictions and limited availability of information in various languages make it more difficult for immigrant communities to access these programs.

Federal investment is absolutely essential for making child care more affordable for families. And where federal programs may exclude children based on their citizenship status, states can provide assistance to families who meet all requirements except citizenship, as Vermont now does.

- Support Family, Friend and Neighbor (FFN) Care providers.

Providers of family, friend, and neighbor (FFN) care—the type of care often performed by immigrant women and preferred by immigrant families due to the enhanced trust, continuity of care, flexible hours, and/or shared language and culture—are often excluded from child care assistance programs. In order for our child care system to meet families’ diverse needs and preferences, it must be inclusive of all types of educators and providers. Broader child care programs and initiatives, including child care assistance programs, should include FFN providers and incorporate supports that are culturally and linguistically relevant and accessible to FFN providers, especially those who are immigrants or who care for immigrant families.

- Increase language accessibility of early care and education programs.

One-third of young children, from birth to age 5, are Dual Language Learners (DLLs) or English Learners (ELs), which means they live with at least one parent who speaks a language other than English in the home. And yet, the vast majority of early childhood programs do not have sufficient language services, depriving children of the accepting, compassionate, and intellectually stimulating environments they deserve—and that all children need for their cognitive, social, and emotional development.

For ELs, the benefits of dual-language early childhood education and care programs are significant. Exposure to a child’s home language while at child care can foster a sense of comfort and familiarity, enabling children to express their needs, thoughts, and emotions more easily. Furthermore, ELs who attend dual-language programs in pre-K and kindergarten have been shown to be more likely to achieve English-language proficiency by middle school, and receiving dual-language early education predicts better academic outcomes and language acquisition than receiving English-only education.

On top of this, without proper language access considerations built in, programs may struggle to share information with immigrant families. Working with trusted, culturally specific community partners can help reach more ELs and their families, providing them with information on how to apply for and enroll in child care programs and maintaining communications with program staff. Having educators who speak the same language as families also supports the relationship with the child’s parent(s), which is crucial for building trust and relaying information about the child’s day and development.

- Make it clear that accessing child care services will not put immigrants at risk.

Immigrants’ applications for visas can be denied on the basis of their dependence on government services, otherwise known as becoming a “public charge.” Although child care-related services are currently not considered in public charge determinations, immigrant parents may receive misinformation, causing concern that by accessing child care services, they could be denied a green card or visa. It is also deeply important that child care spaces have policies in place that deal with interactions with immigration enforcement authorities, emphasizing the well-being of children in all situations.

It is our responsibility to advocate for affordable and accessible child care that is inclusive of immigrant families, so that every child in our country can thrive. All children, regardless of immigration status or family background, deserve equitable access to resources and care.