Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

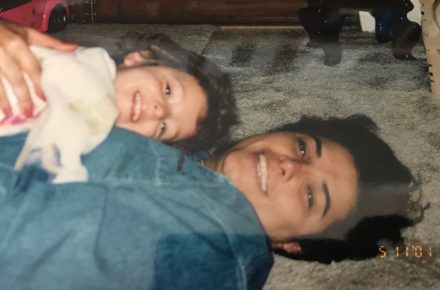

In Search of My Own Lady Bird: Coming of Age as the Daughter of an Immigrant

Growing up, I didn’t understand why my family life felt so different from my friends’. I felt like I had just gotten unlucky, like some act of God had made it so everyone’s mom allowed them to have playdates on school nights, eat Doritos, wear shorts and tank tops to school, wear makeup, date boys, and go to parties but mine. (The list of stuff I couldn’t do got longer as I aged.) I felt completely alone in my experience of a parent-child relationship, not realizing that there are many kids who are exactly like me.

It’s normal for first-generation Americans to come into their cultural identity after high school and begin to realize that this is a universal experience—as evidenced by the popularity of Facebook groups like Subtle Asian Traits, which primarily pokes fun at “FOB-by” (Fresh Off the Boat) habits and memories picked up from Asian immigrant parentage. But why do most of us, especially those who live in majority-white towns, feel so “weird” for our entire upbringing, and why does it take us 18 years to realize that we are not alone?

Imagine if I’d seen just one movie or TV show in my childhood and adolescence that showed me that my experience was normal. Coming-of-age content has almost entirely left out first-generation Americans—especially girls.

Coming-of-age media is a vital part of normalizing the adolescent experience, especially for young women. Middle and high school years are strange and confusing times, and showing the awkward, pimply, and isolating moments of those years onscreen lets young people know that it is okay to not be the most popular, to be confused, to feel alone, or to struggle with dating or friendships. However, virtually none of Hollywood’s coming of-age content – excepting the 2002 British hit Bend It Like Beckham – depicts a parent-child relationship or an adolescent experience that first-generation Americans can relate to.

When I watched Lady Bird, a universally revered, feminist coming-of-age movie, I was excited by all the little moments of teen girlhood I could relate to. However, my overarching thought throughout the movie was, “If I talked to my mom like that, she’d kill me.” While white friends with American parents could speak to how relatable Lady Bird and her mothers’ tumultuous relationship was, I felt entirely out of the loop. This exact exchange has happened time and time again when I or my fellow first-gen friends watch coming-of-age content; Eighth Grade, Edge of Seventeen, and even my personal favorite movie of 2019, Booksmart, represent parent-child relationships that are uniquely white American. From, at worst, watching the otherwise sweet Eighth Grade’s Kayla routinely rip apart her sensitive father (with no prompting), to, at best, seeing the bumbling allyship of Booksmart’s Amy’s parents, I could never see my home life. Lady Bird, Eighth Grade, and now Booksmart are in the “cool girls club” of late 2010s, feminist, heartfelt coming-of-age stories; I too, am a feminist girl coming to adulthood in the same era, but I still feel missing from the story.

The sole piece of coming-of-age content representing first-generation American girlhood right now is PEN15. If I could write a love letter to this raunchy, heartfelt Hulu comedy… well, actually I’m going to right now. Not only does it realistically depict the trials and tribulations of seventh grade, but the character of Maya Ishii-Peters is the biracial, first-gen heroine I have been waiting for. Maya is half-Japanese, half-white, and her relationship with her mother and her cultural identity is constantly tested as she tries to appear cool to her predominantly white, middle school peers. Maya’s reckoning with her cultural identity is a familiar one. She shamefully covers a shrine for her Ojichan with a blanket, caricatures herself and her culture to be considered funny to racist peers, purchases one tiny bag of Cheetos in the hopes that white classmates won’t look for snacks in her home (they only find “fish heads” in her fridge, to Maya’s mortification), and loudly whines when her mother asks her white friend to take off her shoes upon entry—something my white American friends were constantly reminded about while trying to run up my stairs, shoes still on. Seeing these little moments that I and so many other children of immigrants can relate to consistently made me tear up—from laughter, but also from relief that I’m not the only one.

The most heartfelt moment comes in the episode “Anna Ishii-Peters,” when Maya sees her tough-love mom be softer and kinder with her white best friend than she’s ever been with her. Following tearful outbursts from Maya, who is anxious her mother doesn’t love her because she is so strict, her mother hugs and reassures her, sings her a lullaby in Japanese, and they fall asleep side by side. This is a direct challenge to the whitened Asian immigrant “tiger mom” stereotype, which can force Asian moms into a one-dimensional box; it shows how tough love often can still emphasize the “love” part. While my mom is a very proud, self-titled “tiger mom,” she also never misses an opportunity to tell me she loves me. PEN15 gives nuance and truth to the Asian immigrant mother-and-daughter story, and for the first time, showed me a parent-child relationship like mine.

Seeing the experiences I thought made me abnormal represented on television was very powerful, and soothed some of my residual childhood shame surrounding being first-generation. That is the impact of seeing our stories, and we only have more to tell.

While only PEN15 has shown the stories of first-generation American girls so far, more is on the horizon. As diversity onscreen has pulled success in Hollywood and on television, writers and actors of color are getting the chance to tell new stories. Currently, projects by comedy superstars Mindy Kaling and Nasim Pedrad, aiming to show the teenage lives of first-generation Americans, are in the works. Kaling’s Netflix series will follow the life of a 15-year-old first-generation Indian-American girl, and Pedrad’s TBS comedy will allow her to play a teenage Iranian-American boy, trying to become popular in his predominantly white school. These projects could not only help normalize the first-generation coming of age experience in popular culture, but for the first time, show children of immigrants an adolescent experience like theirs on TV. And I will be excitedly tuning in.