Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

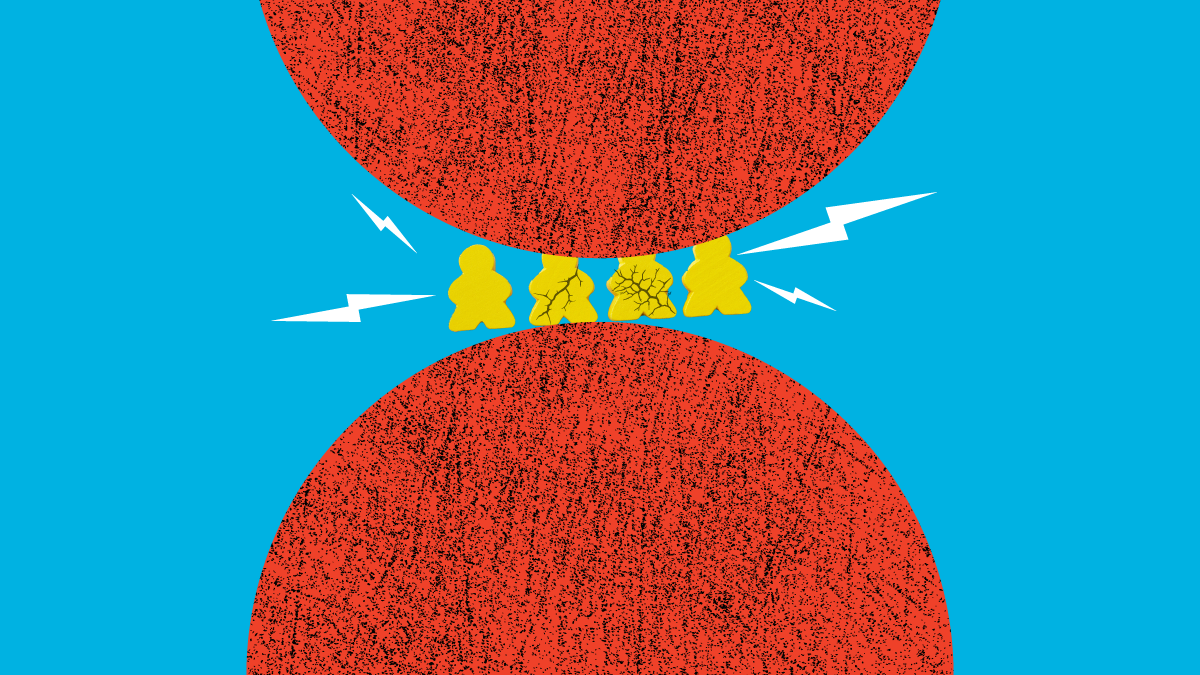

Expulsions in Early Childhood Hurt Infants, Toddlers and their Families

Suspension and expulsion of young children from prekindergarten and child care, by depriving them of opportunities to learn in their early years, can have a direct impact on their future. These expulsions especially affect working families who struggle to find affordable child care and who cannot easily find alternative arrangements. Recent studies show that suspension is a surprisingly common punishment used in child care settings for infants and toddlers ages zero to three. The reauthorization of the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) calls on states to create policies that will reduce expulsion and suspensions of these young children and reduce the negative behavioral outcomes these suspensions cause.

Suspension and expulsion of young children from prekindergarten and child care, by depriving them of opportunities to learn in their early years, can have a direct impact on their future. These expulsions especially affect working families who struggle to find affordable child care and who cannot easily find alternative arrangements. Recent studies show that suspension is a surprisingly common punishment used in child care settings for infants and toddlers ages zero to three. The reauthorization of the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) calls on states to create policies that will reduce expulsion and suspensions of these young children and reduce the negative behavioral outcomes these suspensions cause.

Every year, 50,000 preschoolers are suspended from public preschool programs, with Black children much more likely than other children to be suspended. This figure does not include all the preschool students that are suspended from private programs. A study in Chicago found that 42% of child care programs that enroll children from birth to three expelled at least one child in the previous year because of behavior. A study of Philadelphia centers found that 26% of child care programs had expelled at least one child in the past year and that toddlers were just as likely as preschoolers to be asked to leave their child care setting.

The stress from these experiences can stay with young children and lead to negative results in their lives. Many children are expelled for behaviors that are actually typical for a young child or expected stages of their development—such as this three year old who was suspended from her preschool for too many potty accidents. These expulsion and suspensions can hurt social-emotional development and actually worsen unhealthy behavior for children as young as toddlers, rather than addressing the cause of those behaviors. Children suspended for misbehavior may be acting out for any number of reasons, including stress in the home—and suspension only exacerbates the stress for the children and their families, which in turn can lead to worse behavior in the classroom.

Children and their families can also be harmed by “soft expulsion,” where programs do not formally remove from a child care program, but repeatedly call parents to pick up their child early, tell parents their child should take a week off, suggest the child isn’t the right fit for the program, or take other steps that make it difficult for the child to remain with the program. Most parents who can’t afford to keep missing work or leaving work early to pick up their child have to choose between making a living to support their family or seeking another child care setting. Such instances, which are technically voluntary, are often not reported in studies on expulsions in early education, keeping counts of expulsions artificially low.

Thankfully, with the CCDBG reauthorization law’s provisions aimed at preventing suspension and expulsion in early child care settings, some states are beginning to act to address this problem. States such as Arkansas, Illinois, and Ohio have proposed or passed legislation that will help mitigate the number of expulsions and “soft expulsions” happening in child care centers. And if your state, community, or individual child care program has not yet taken such steps yet, the National Women’s Law Center has put together a took kit that gives you suggestions for what you can do if you feel like your child care program is discriminating against children through expulsion and suspensions. State and local policymakers, child care programs, advocates, and parents all need to take action to ensure children have stable, supportive early care and education environments that encourage—not harm—their healthy development.