Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

It’s Time for Equal Pay Legislation in Congress

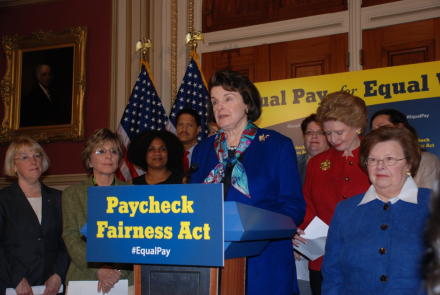

January is full of milestones in the fight for equal pay. This week marks the 10th Anniversary of the enactment of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act – the first piece of legislation that President Obama signed into law, which importantly allows women to challenge unlawful pay discrimination 180 days after any discriminatory paycheck. Earlier this month, Congress introduced the Raise the Wage Act, which would raise the minimum wage from $7.25 an hour to $15 an hour by 2024. Today, Congress re-introduced the Paycheck Fairness Act, which would update and strengthen the Equal Pay Act of 1963 to ensure that it provides robust protections against sex-based pay discrimination.

Pay discrimination still exists.

We need this action because the gender wage gap unfortunately still exists – women working full time typically are paid 80 percent of what their male counterparts are paid. And wage gaps are much worse for many women of color: Black women typically make only 61 cents, Native women only 58 cents, and Latinas only 53 cents, for every dollar paid to their white, non-Hispanic male counterparts. While Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) women make 85 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men, many AAPI communities experience drastically wider pay gaps.

One major driver of the wage gap is pay discrimination. Of all forms of discrimination, pay discrimination is among the most difficult to detect and address. Because of a culture of secrecy around pay, women can be paid less than the men working next to them for years without realizing it – as Lilly Ledbetter discovered. She started working at Goodyear Tire and Rubber plant in Alabama in 1978 as the only woman doing her job. It was not until 19 years after working at Goodyear that Ledbetter found out she was being paid less than her male counterparts – through an anonymous note. She brought a Title VII discrimination suit against Goodyear that eventually made its way up to the Supreme Court. In a 5-4 decision in 2007, the Court held that Ledbetter could not recover any damages because she brought her suit too late – she needed to have filed her lawsuit within 180 days of her initial pay conversation with Goodyear.

In 2009, President Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act into law, which addressed the Supreme Court’s harmful decision in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company. Employees were no longer barred from bringing a Title VII suit against their employers because they brought their suit outside the unrealistic 180 days of their initial pay conversation – they now could assert their rights within 180 days after any and every discriminatory paycheck.

The Ledbetter Act was an important step forward in the fight against pay discrimination and to close the gender wage gap, and the Wage Act and the Paycheck Fairness Act would build upon this progress.

The Raise the Wage Act will boost pay for women, especially women of color.

Another major driver of the wage gap is women’s overrepresentation in low-wage jobs. Women are close to two-thirds of the workforce in jobs that pay the minimum wage or just a few dollars above it, as well as two-thirds of workers in tipped jobs. The Raise the Wage Act would raise the federal minimum wage from $7.25 an hour to $15 an hour by 2024, then index the minimum wage so that it continues to rise along with wages overall. It would also end unfair exclusions for tipped workers, people with disabilities, and youth, so that they too can benefit from a decent minimum wage.

The Economic Policy Institute estimated in 2017 that increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2024 would give more than one in three working women a raise, including 43 percent of Black working women, 38 percent of working Latinas, 32 percent of white working women, and 20 percent of Asian working women. Overall, women are the majority of workers who would see their pay go up—making the Raise the Wage Act another critically important step to secure fair wages for working women.

Moreover, the Raise the Wage Act would make women less vulnerable to sexual harassment from customers because women in tipped jobs would have a paycheck they can count on – not a cash minimum of $2.13 an hour that leaves them to rely on tips from customers for nearly all of their income.

The Paycheck Fairness Act will provide robust protections against sex-based discrimination.

The Paycheck Fairness Act would update and strengthen the Equal Pay Act of 1963 to ensure that it provides robust protections against sex-based pay discrimination. It would:

- Prohibit employers from relying on salary history to set pay when hiring new employees so that salary discrimination does not follow women from job to job.

- Close a loophole in the employer affirmative defense under the Equal Pay Act that has enabled employers to pay women less than men for the same work without a legitimate business reason related to the job.

- Allow women to receive the same robust remedies for sex-based pay discrimination that are currently available to those subjected to discrimination based on race or ethnicity.

- Promote pay transparency by barring employer retaliation against employees who voluntarily discuss or disclose pay, and requiring employers to report pay data to the EEOC.

This historic new Congress, which includes record numbers of women who ran and won on issues central to women’s economic well-being, has the opportunity to build upon the progress of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act and to advance equity, dignity, and safety for women and families by passing the Raise the Wage Act and the Paycheck Fairness Act. Women and families cannot be shortchanged any longer.