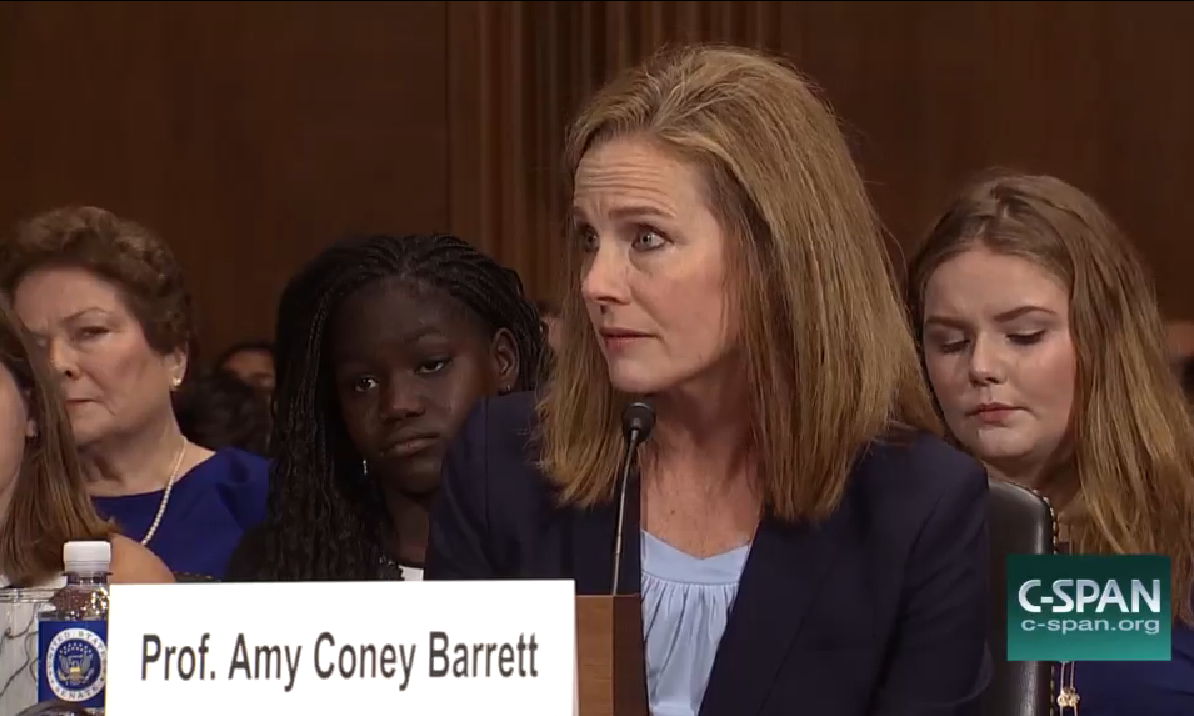

Amy Coney Barrett’s Troubling Writings on Judicial Precedent

As the Senate Judiciary Committee prepares to vote on the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals today – along with a bunch of other nominees with concerning records who got crammed into a single confirmation hearing – we wanted to highlight one particularly troubling area of her record: her writings on judicial precedent and stare decisis.

As the Senate Judiciary Committee prepares to vote on the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals today – along with a bunch of other nominees with concerning records who got crammed into a single confirmation hearing – we wanted to highlight one particularly troubling area of her record: her writings on judicial precedent and stare decisis.

Respect for judicial precedent and stare decisis are cornerstone principles of our judicial system. Barrett has written a lot about these issues as a law professor, and those writings raise serious concerns.

For example, Barrett wrote approvingly in one article that when the Supreme Court is willing to revisit its precedents in constitutional cases, it “helps the Court navigate controversial areas by leaving space for reargument. . . .” This is language that could encourage litigants to challenge prior Supreme Court decisions. Indeed, Ms. Barrett suggested in the same article that the staying power and force of decisions by the Supreme Court depends, at least in part, on people’s willingness to challenge them. Specifically, she wrote, “The force of [superprecedents] derives from the people, who have taken their validity off the Court’s agenda. Litigants do not challenge them.” So for example, Barrett wrote that “the public response to controversial cases like Roe [v. Wade] reflects public rejection of the proposition that stare decisis can declare a permanent victor in a divisive constitutional struggle. . . .”

Barrett has also downplayed the harm that overturning legal precedents may cause to the institutional legitimacy of the Supreme Court and to people’s reliance on those earlier cases. In another article, she argued that if “a litigant demonstrates that precedent demonstrably conflicts with the statutory or constitutional provision it purports to interpret,” the reliance interest (which is a factor the court should consider when deciding whether or not to maintain the precedent) should be given less weight. These statements suggest an approach to judging that openly and routinely questions judicial precedents – while disregarding the disruption for those who have come to rely on the law.

Together, these statements raise serious questions about how Barrett, if confirmed as a circuit court judge, would interpret, apply, and follow precedent, including Supreme Court precedent. Her prior writings consistently suggest that she believes precedents like Roe and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey should be considered weaker — and are susceptible to challenge, both by judges by the public. Indeed, by defining the strength of precedents in terms of the willingness of litigants to challenge them, she signals her openness to considering repeated, ideological challenges to cases like Roe v. Wade.

Although Barrett stated at her hearing that she would follow Supreme Court and circuit precedent (including Roe and Casey) if confirmed, her testimony is difficult to square with a long and consistent written record. The question for Senators on the Committee is whether they will choose to credit what she has said as a nominee over what her record consistently demonstrates throughout her career. The stakes are too high for women for them to do so.