Make your tax-deductible gift by December 31—every gift matched, up to $150,000!

In this moment, the future of our rights, our bodily autonomy, our freedom feels uncertain. What we do next will make a difference for decades to come.

Make your tax-deductible gift by December 31—every gift matched, up to $150,000!

In this moment, the future of our rights, our bodily autonomy, our freedom feels uncertain. What we do next will make a difference for decades to come.

Double your impact in the fight to defend and restore abortion rights and access, preserve access to affordable child care, secure equality in the workplace and in schools, and so much more. Make your matched year-end gift right now.

I didn’t use to spend a lot of time examining my identity—I’m a woman of color, I’m Indian American, I’m Brown. That already felt like a lot of labels and I’ve been content to stop there. But my relationship with who I am is so much more complicated than that, and during AANHPI Heritage Month, I wanted to be brave and face something that I am still struggling to articulate, to look at directly, which is my own internalized racism.

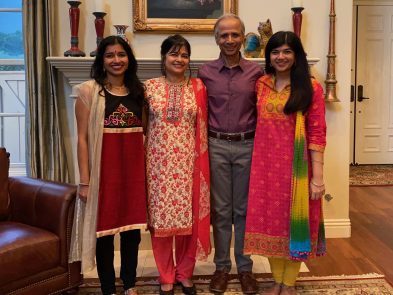

Growing up, I never thought of myself as any different from my white peers. My childhood was a loving, plucky, American coming-of-age story set in suburbia. My parents seamlessly wove their immigrant culture into our lives in ways I didn’t fully register, celebrating Diwali and Eid along with Christmas, singing Marathi songs along with Broadway hits. I felt confused, and then defensive, when my friends asked if I ate Indian food every day or spoke “Indian” at home. Of course, I didn’t. I was just like them. And we ate Indian food every few weeks.

Childhood and adolescence are awkward, fleeting stages of life and no matter how many times you’re told to be yourself, the reality is that standing out in the wrong ways can be mortifying. I went to small schools without the option of anonymity, where you were defined by who you weren’t as much as who you were. And I—realizing that even if I thought of myself like “everyone else” (read: white), I had too much melanin to be seen that way—decided that the solution was to distance myself from my Indianess as much as possible. I’m not good at math, I protested. On special occasions, I don’t wear a shalwar kurta; I wear a dress, I clarified. I don’t even speak Hindi or go to temple, I made sure everyone knew. I was trying to be cool, and fun, and accepted. It was cruel—not just to myself but to the other AANHPI students that I was implicitly putting myself in opposition to.

It’s difficult to look back on those moments and face my own naivete and desire to conform, but I also feel sadness for my younger self, who thought that insults about her body hair and demands to “go back to where you came from” were just a part of growing up.

I give a lot of credit to my education for helping me change perspective. Learning about the model minority myth, the pay gap, the fraught immigration history, the perpetual foreigner stereotype, helped me realize that when I was dismissive and self-deprecating, I was unknowingly contributing to a tradition of racism and xenophobia. I realized that the people I was constantly trying to prove myself to were not the company I wanted to keep. And being surrounded by so many unapologetic AANHPI and other POC made me wonder why I couldn’t do the same. Equally important, was that the world changed, and I changed along with it. In a time of growing white supremacy, when attacks against AANHPI communities are on the rise, when people who look like me are banned from immigrating, the most defiant thing I could do was wear my Indianess as a badge of honor and love. Embracing my race became an act of revolution.

AANHPI Month means a lot to me—it’s a celebration of our community and its achievements, but it’s also a personal celebration. I’m fully aware how my past behaviors don’t match the person I am now. But there’s importance in confronting the parts of yourself that feel uncomfortable. We’re all learning and growing and unpacking the years of institutional influences that seep into our bones, despite the best efforts of our parents, educators, and mentors. Naming that experience is how I believe we build empathy and solidarity within and outside of our community. I still feel awkward trying to navigate spaces where I feel too Indian and others where I am not Indian enough, but I’m proud of how far I’ve come. And that’s what this month is about: feeling pride for who you are, in this moment, right now.