Speaking Up for Survivor Justice in the Senate

On April 2, 2019, the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions (HELP) held a hearing on campus sexual assault and ensuring students safety and rights in the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. This was a big deal, and that’s partly because the U.S. Department of Education recently proposed changes to its Title IX rules addressing how schools need to respond to sexual harassment. We don’t know when the final rules will be issued, and it’s important that everyone knows that Title IX currently remains unchanged.

On April 2, 2019, the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions (HELP) held a hearing on campus sexual assault and ensuring students safety and rights in the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. This was a big deal, and that’s partly because the U.S. Department of Education recently proposed changes to its Title IX rules addressing how schools need to respond to sexual harassment. We don’t know when the final rules will be issued, and it’s important that everyone knows that Title IX currently remains unchanged.

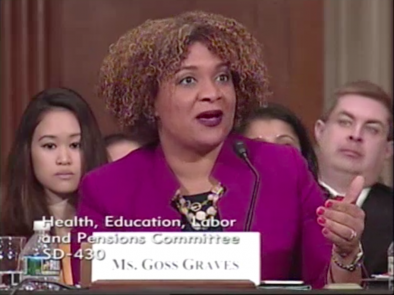

But as we’ve said many times, if these terrible and misguided rules were to go into effect, they would roll back Title IX protections for survivors of sexual violence, create contradictory and confusing requirements for schools, and give special rights to alleged harassers and rapists over survivors. NWLC’s President and CEO, Fatima Goss Graves, used her opportunity to testify before the Senate Committee to not only explain why the Department’s proposed rules would cause more harm to students, but to lay out guiding principles for a campus process that’s prompt, equitable, and impartial.

For Fatima’s full, written testimony, click here.

Fatima’s Opening Remarks:

Thank you, Chairman Alexander, Ranking Member Murray, and Members of the Committee. I’m Fatima Goss Graves, President and CEO of the National Women’s Law Center, and I appreciate the opportunity to testify today.

The National Women’s Law Center was founded the same year that Title IX was passed, we have worked to address sex discrimination in schools, including harassment, since that time. I have personally been engaged deeply in this topic, representing clients, serving on the Clery Rulemaking roundtable, and on the ALI project on this topic.

Study after study shows that students in college continue to experience extremely high rates of sexual assault. More than one in five women, one in 18 men, and nearly one in four transgender and gender-nonconforming students.

The students we hear from at the National Women’s Law Center report that they were discouraged from reporting in the first place, that they have been met with delays, that the process that they have experienced was extremely unfair, that the trauma they experienced both from their assault and from going through their school process stays with them far after they leave the university. For some what is at stake is whether they can continue to stay in school at all.

Any reauthorization of Higher Education Act should take this into account, including also the principles of the Clery Act and Title IX, and the existing procedures to adopt and enforce procedures to address sexual assault that is prompt, equitable, and impartial.

Unfortunately, recently, the Department of Education proposed changes to its Title IX rules. If these rules were to go into effect, schools would be forced to ignore a lot of sexual assault and would be required to have unfair and harmful processes that we believe would deter survivors from coming forward in the first place. The response to these proposed rules was swift, with thousands of people around this country urging the Department to abandon this misguided plan.

Many reminded the Department of guiding principles that are already imbedded in Title IX and Clery. I don’t have time to go through all of them but I want to highlight a few.

First, fair processes require all parties to have timely and clear notice in advance of meetings or hearings – we have heard of schools failing to do this, to the detriment of all students. In addition, it requires effective interim measures that preserve the complainant’s equal access to education – this may be as simple as changing a dorm or a classroom. It also requires resolving sexual assault complaints with the same evidentiary standard used in other civil rights proceedings, which is the preponderance of the evidence standard. Schools should not subject sexual violence to a higher and unique standard. That’s a theme that you will hear from me.

In addition, campus processes should treat all students involved equitably. This means that both respondents and complainants should have the same rights to have witnesses, and the same rights to have evidence, and the same rights to appeal. It would be unfair to allow only one side to appeal a process that is decidedly unfair.

Finally, I want to take a minute to address the issue of cross-examination. Some have argued, including the Department of Education in its unfortunate proposed rule, that cross examination is required to ensure that a process is fair. Here is where I strongly disagree. These are not court rooms. In these proceedings students typically don’t have counsel, they don’t have rules of evidence that apply, there isn’t trial procedure, and there isn’t meaningful protection from inappropriate, irrelevant and victim blaming questions.

Most fundamentally, any rule requiring colleges and universities to conduct live, quasi-criminal trials with live cross-examination, when no such requirement exists for addressing any other form of misconduct at schools, communicates the message that survivors are uniquely unreliable. Implicit in such a requirement is a deep-rooted skepticism of sexual assault itself.

It’s already an issue that is dramatically underreported. This will only be exacerbated if students who report must undergo traumatic and unnecessary procedures.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that student survivors care deeply about the fairness of their school systems. They have as much interest in the outcome of their complaint as the student who is responding to their allegation. Each are harmed when schools implement unfair processes. This is especially true for survivors who are facing multiple forms of discrimination. Again and again we hear from black and brown women in particular whose accounts are less likely to be believed in these process and they are especially vulnerable to an unfair process.

It’s time to match the seriousness of the survivors who are demanding accountability from their schools.

Thank you for the opportunity to be here today and I look forward to any questions.