Sandwiched: My Mom’s Life and Lessons as a Dual Caregiver

I have always admired my mom’s strength and resilience: her willingness to sacrifice her own aspirations to allow me to grow, her eagerness to spend time with me (even after a long day of work at the hospital), and her desire to make me feel loved every day.

Over the years, I’ve watched my mom take on more and more responsibility as she has stepped into the role of caring for her own mother, whom we call Maya, while still showing up for me and my older brother Jamie in countless ways. In my senior year of high school, Maya moved into our house because of her worsening dementia. At the same time, I was struggling mentally and emotionally, overburdened by my school work and anxious about the future. I saw how difficult it was for my mom to balance both of our needs, but she did it with as much poise and grace as she could. I feel so lucky to have had her by my side through it all.

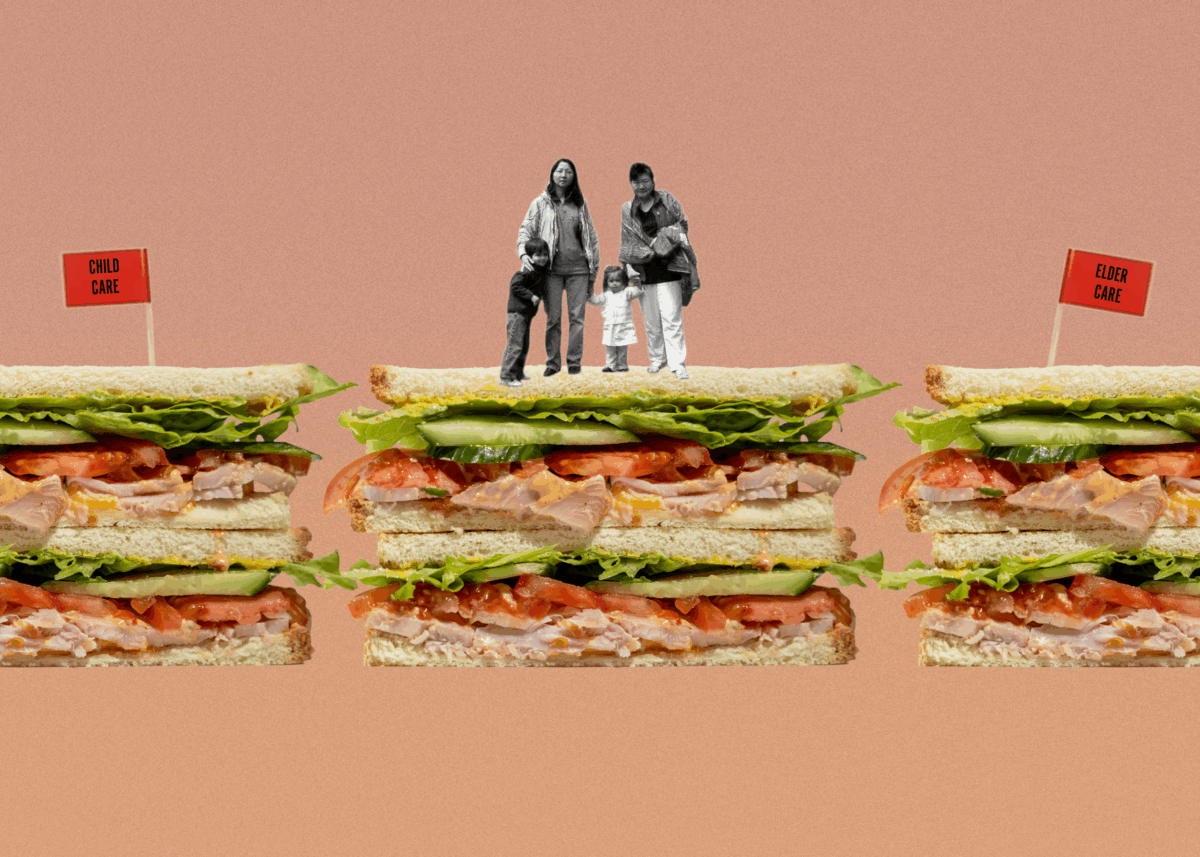

My mom’s experience reflects a growing and often overlooked reality: the emotional and physical toll of being part of the “sandwich generation,” adults who are caring for their aging parents while also raising their children. Pew Research Center estimates that a quarter of all adults in the United States (70 million) are part of the sandwich generation. Like my mom, millions around the country are constantly navigating the delicate and demanding role of being a dual caregiver.

I sat down with my mom to learn more about how she balances this responsibility, and what she’s discovered along the way. Her answers offer insight into the emotional toll and strength required to care for multiple generations—and how love, family, and responsibility shape that journey.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

What has it been like serving as a caregiver to me and Jamie, while simultaneously having to care for Maya?

There wasn’t quite as much overlap as there could have been, since Maya was independent until Jamie was already out of the house and you were in your last year of high school when she moved in with us. I know lots of other people who had to deal with sick parents while raising much younger kids, and that’s definitely much harder.

But even before she moved in with us, of course, there were things I had to help her with—driving her here and there, making sure I took her to her doctor’s appointments and all that. And I was also still working, which made it that much harder at the time. I think juggling all that was obviously challenging, but I was fortunate enough that once Maya moved in, I was retired, so I could focus all my attention towards taking care of Maya and helping you out.

It was difficult, but it was expected that as her daughter I would care for her in her old age, and I would not have had it any other way since she sacrificed so much of her life to take care of us. And Maya helped so much with raising you and Jamie too, which was a big help to me while I was more busy with work. Overall, it wasn’t a sacrifice that was too difficult for me.

In what ways has Maya’s dementia and her limited proficiency in English made your caregiving role more difficult?

Now that Maya is at a memory care facility and not living with us, the minute-to-minute is not my responsibility. But I do feel, with anybody living with dementia, you really have to be an advocate for your loved one. If you don’t have anybody speaking up for you, you can easily get lost in the shuffle, especially with the ratio of caregivers to residents being pretty low. Trump’s Medicaid funding cuts may make things even worse. You really have to make sure that your loved one gets the care they really need. You have to have advocates, and you have to have people who are paying attention. You have to have people who are speaking up for your loved one. Maya has a triple whammy—having dementia, not speaking English, and not being able to hear—so it would be easy for the caregivers to just ignore her. So, it’s important for the family to be assertive and really make sure that she gets the care she needs.

I think it’s true in most families that the majority of responsibilities for caregiving for parents often falls onto one of the children, whether it’s because they’re more willing to do this kind of responsibility or because the other siblings are not able to. Even though my sister lives far away, she’s supportive and she helps as much as she can. I think it works okay, but I do still have a lot of mental stress about Maya day-to-day. I’m always stressed that she’s going to make a huge mess with her clothes or lose things or get rid of things. So it’s really nice when my sister is here. It’s a big load off my mind when she’s here.

Are there things you wish you had known before you were required to take on this role?

I knew from the start that this was the expectation, that all three of us siblings were going to take care of our parents when they needed help. I knew it was coming, and it was a little bit easier because my dad passed away so many years ago, so I wasn’t dealing with two older parents. The main thing that surprised me was the trajectory of her dementia. It happened so fast, with her hallucinations. I wasn’t really aware that could happen with Alzheimer’s, so when it happened, it was very upsetting. I was just feeling so hopeless about how to help her, and that was really challenging.

It’s also difficult when you have a career. You always have that push and pull, always feeling kind of guilty. When you’re working, you feel guilty you’re not with your kids. And when you’re with your kids, you feel guilty you’re not doing your work. That’s a big challenge for working women, and adding the responsibility of taking care of your parents is very stressful.

How do you deal with the stress of holding two generations together? How do you recommend individuals get ready to face that burden?

I think it depends on the situation. The important thing for people is to have a good support network, whether that’s other siblings, other family members, or even friends. It’s important to have downtime—time where you can do something that’s pleasurable for yourself or time where you can just vent to a friend.

You definitely need to find time to give yourself a break, because otherwise you’ll get burned out and that wouldn’t be good for anyone. You won’t be able to help anybody if you can’t function.

How can society do a better job in supporting individuals who are part of the sandwich generation?

Some countries in Europe have affordable and accessible senior centers where you can drop your family member off and they can socialize all day, and then you can pick them up at night. It would be amazing if they had more places like that for people in the United States, not only for the younger people doing the caring, but also for the older generation because socialization is important as a deterrent to developing things like dementia.

For kids, we have child care, but it’s so expensive. Especially for low-income people, child care can amount to basically as much as you’re making, so either you work and pay for child care (and then you can’t save money for the future), or you stay home and don’t advance your career or make money. It’s a double-edged sword.

Places like Europe and Canada have better maternity leave. Some lawmakers are also trying to implement universal child care or child care that’s free to parents. If our government had better policies for child care and for elder care, I think it would really make a huge difference to the sandwich generation.