Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQI+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

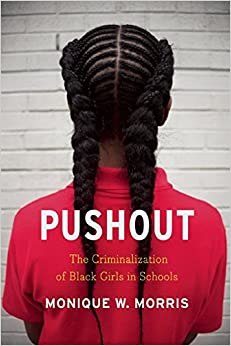

Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools

Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools is a must read for anyone who has loved, known, taught, considered or judged a Black girl. The book powerfully addresses pushout, which is the structural racism and the cultural barriers that push Black girls out of the classroom and to the outer brinks of society. Black girls are suspended at six times the rate of white girls, and they make up only 17 percent of girls in public schools but almost half of school related arrests. Monique Morris challenges us to rethink how we perceive, teach and treat Black girls by using the voices of young Black girls to explain what the data tells us— that these girls are disproportionately pushed out of the classroom through unfair discipline policies.

Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools is a must read for anyone who has loved, known, taught, considered or judged a Black girl. The book powerfully addresses pushout, which is the structural racism and the cultural barriers that push Black girls out of the classroom and to the outer brinks of society. Black girls are suspended at six times the rate of white girls, and they make up only 17 percent of girls in public schools but almost half of school related arrests. Monique Morris challenges us to rethink how we perceive, teach and treat Black girls by using the voices of young Black girls to explain what the data tells us— that these girls are disproportionately pushed out of the classroom through unfair discipline policies.

The gift of this book is in the voices of the girls who have been pushed out of schools. As teachers, researchers, and policymakers who are interested in education, we often make decisions about discipline policies without the voices of those most affected. We should be working with, and on behalf of all girls—including African American girls—to support and enhance school performance, but they are consistently left out of the conversation.

Black girls are more likely to be suspended for challenging ideas on how girls should behave, present and express themselves. In Ohio in 2012-13, Black girls received 16.3 out-of-school suspensions for disobedience or disruption (a subjective and arbitrary category) per 100 Black girls enrolled while white girls only received 1.5 out-of-school suspensions for disobedience or disruption per 100 white girls enrolled. Reading this book has challenged my perceptions of young Black girls who are struggling to be seen, heard, understood, and respected by offering their perspective. The girls in this book engaged in physical, emotional and verbal fights for freedom. “I just got a smart mouth. I don’t be meaning for it to come out like that, but if there’s something on my mind and my heart, I just say it” Malaika says in the book. Her smart mouth landed her in the principal’s office for three days. Stacy describes her experience of being suspended and expelled several times in elementary and middle school for fighting. “Stacy framed her behavior as a tendency to get in trouble, but I see her trigger as anything (or anyone) that might interfere with her own visibility politics. Stacy was triggered by a fear of being ignored.” Black girls like Malaika and Stacy scream for attention, to be appreciated for their individuality, or to be accepted by those who can’t seem to hear their screams of frustration and disillusionments with their life circumstances.

We have to do a better job of supporting and understanding Black girls. Reading this book is the first step. We should do everything in our power to understand Black girls and limit zero tolerance policies and other exclusionary and extreme discipline. Our goals should be to keep our students in school and not push them out. These girls are more than “defiant,” “a smart mouth” or “a fighter.” Black girls are beautifully complex with a lot of gifts to give to the world. They deserve to feel safe and nurtured in schools. As Ms. Morris says, “Love is corrective.”