Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

Attacks on Abortion Are Attacks on Maternity Care

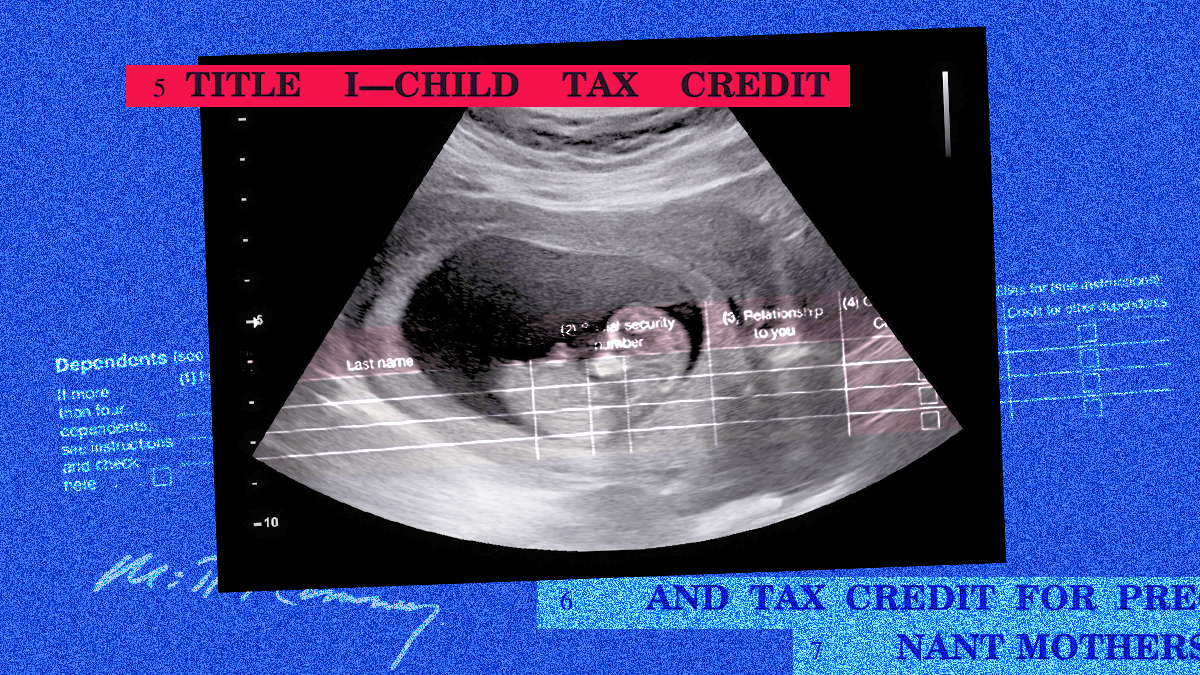

We all know and love phrases like “abortion is health care” and “abortion saves lives.” But here is another important phrase that you might not be thinking about: “abortion is maternity care.”

Maternity care encompasses care provided to a person before, during, and after their pregnancy—and yes, this includes abortion. So, let’s call state abortion bans what they are: intentional and direct attacks on maternal health and well-being. And even in states where abortion is technically legal, in-person care is too often inaccessible because clinics are subject to stringent legal restrictions, understaffed, or too far away. As a result of abortion bans, restrictions, and other barriers, pregnant people, and particularly pregnant women who are Black, Indigenous, and Latina, face serious hurdles to accessing vital care and suffer devastating consequences.

Areas in the United States that lack meaningful abortion access are called “abortion deserts,” and these deserts have increased significantly since Roe v. Wade was unjustly overturned. The growing number of these deserts reflects the concerning reality that more and more women of reproductive age live in states where abortion is either unavailable or severely restricted.

Not only do abortion bans and restrictions take away or make more difficult people’s access to abortion, but they also have a dangerous effect on all forms of health care, including other types of maternity care. In states where abortion is illegal or restricted, practicing obstetric and gynecologic care has become more perilous as providers are forced to determine what type of care is and is not permitted. Providers may also be forced to compromise the standard of care for a particular patient. Pregnancies and pregnancy outcomes are subject to greater scrutiny—pregnant people seeking needed care and their providers who offer such services risk significant repercussions, including criminalization. As a result, some doctors are fleeing states with abortion bans, new doctors are hesitant to accept jobs in those states, and some maternity units are closing entirely. In many areas where abortion is inaccessible, so is other basic maternal health care.

As a result, pregnant people living in abortion deserts may also live in areas where other maternity care is inaccessible, or “maternity care deserts,” and be forced to travel long distances, sometimes even out of state, to obtain other types of necessary maternal health care. And just like with abortion care bans, maternity care deserts disproportionately affect communities already facing disinvestment, such as Black, Latina, Indigenous, and low-income communities, where people are less likely to have access to reliable transportation, child care, or necessary funds to travel for care. Indigenous people are far more likely than other populations to live a significant distance from a hospital with an obstetric unit. March of Dimes estimates that one in four Native American babies and one in six Black babies “were born in areas of limited or no access to maternity care services” and that “approximately 2.2 million women of childbearing age and almost 150,000 babies are affected” by maternity care deserts.

In fact, an estimated 3.7 million women of reproductive age in the United States live in a county without access to abortion and with no or low access to maternity care. The overlap of these “maternity care deserts” and “abortion deserts” could lead to horrendous results. The United States already has a maternal mortality rate several times higher than other high-income countries. And because of a persisting legacy of discrimination, unequal distribution of resources, and inequitable access to care, Black women are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women. This grim reality for many pregnant people in the United States will likely only get worse for those with limited access to both abortion care and other types of maternity care. For example, women who do not receive prenatal care, including screening for depression, are up to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than those who do receive care. Needing to travel long distances to access maternity care may increase risks of infant mortality and pregnancy complications. And pregnant people who do not access mental health services during or after their pregnancies can experience long-term negative impacts on themselves and their babies.

We also already know that abortion bans are deepening the existing maternal health crisis in the United States, with disproportionate impacts on Black, Latina, and Indigenous women who are overrepresented in abortion ban states and experience existing difficulties accessing other maternity care. Following the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe, areas with limited abortion care have higher rates of maternal mortality and infant death. Another study found that women in states with abortion bans are nearly three times more likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth or soon after giving birth than women in states without abortion bans and had higher overall death rates for women of reproductive age. Unsurprisingly, women of color were disproportionately impacted. As abortion bans continue to reduce access to other critical maternity services, pregnant people in the United States will suffer even more.

The far-reaching consequences of abortion bans and restrictions are clear: people are forced to carry unwanted pregnancies and deliver in a country with inadequate maternity care and unconscionably high maternal mortality rates. As abortion bans proliferate and maternity care access worsens, pregnant people’s lives, health, and futures are put in danger. Black, Latina, and Indigenous women, as well as other populations already facing systemic disinvestment, are most harmed. Extremist anti-abortion lawmakers love to claim to be dedicated to the health and well-being of women and babies, but the reality is quite the opposite—widespread, coordinated attacks on abortion rights significantly worsen access to maternity care for all pregnant people.